View of the CAYC’s video production laboratory, ca. 1975. Photo: Pedro Roth. Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC) Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. Copyright Archivo Roth

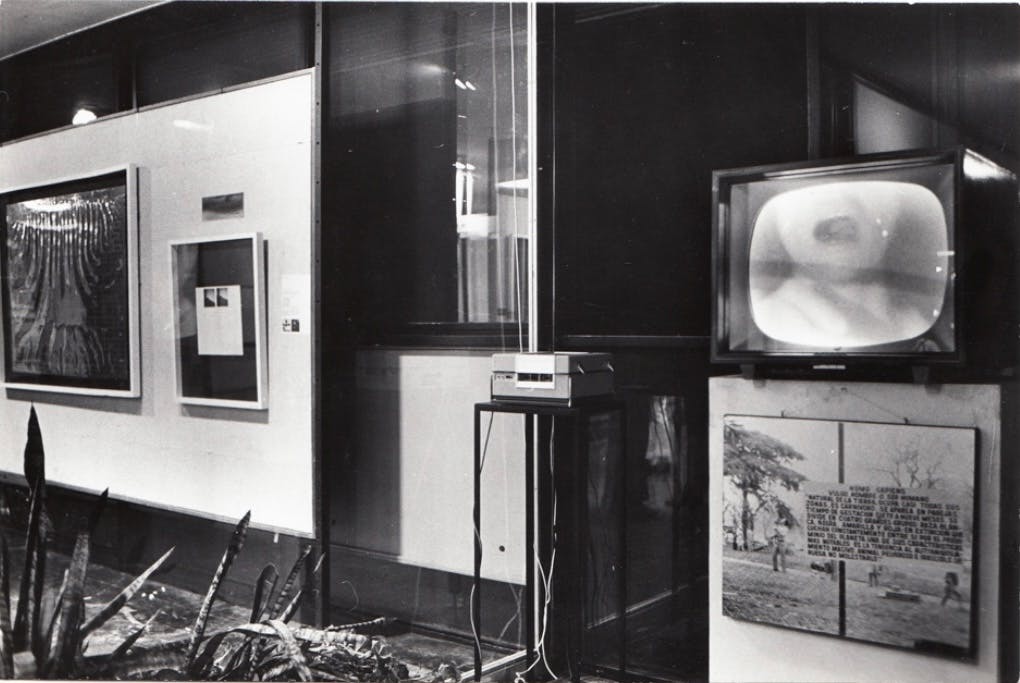

Fig. 1: Entrance to the CAYC’s Buenos Aires gallery space, ca. 1973. Photo: Pedro Roth. Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC) Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. Copyright Archivo Roth

Fig. 2: View of the CAYC’s video production laboratory, ca. 1975. Photo: Pedro Roth. Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC) Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. Copyright Archivo Roth

The Writer in Residence series offers scholars the opportunity to conduct research on Latin American art through materials in the ISLAA Library and Archives.

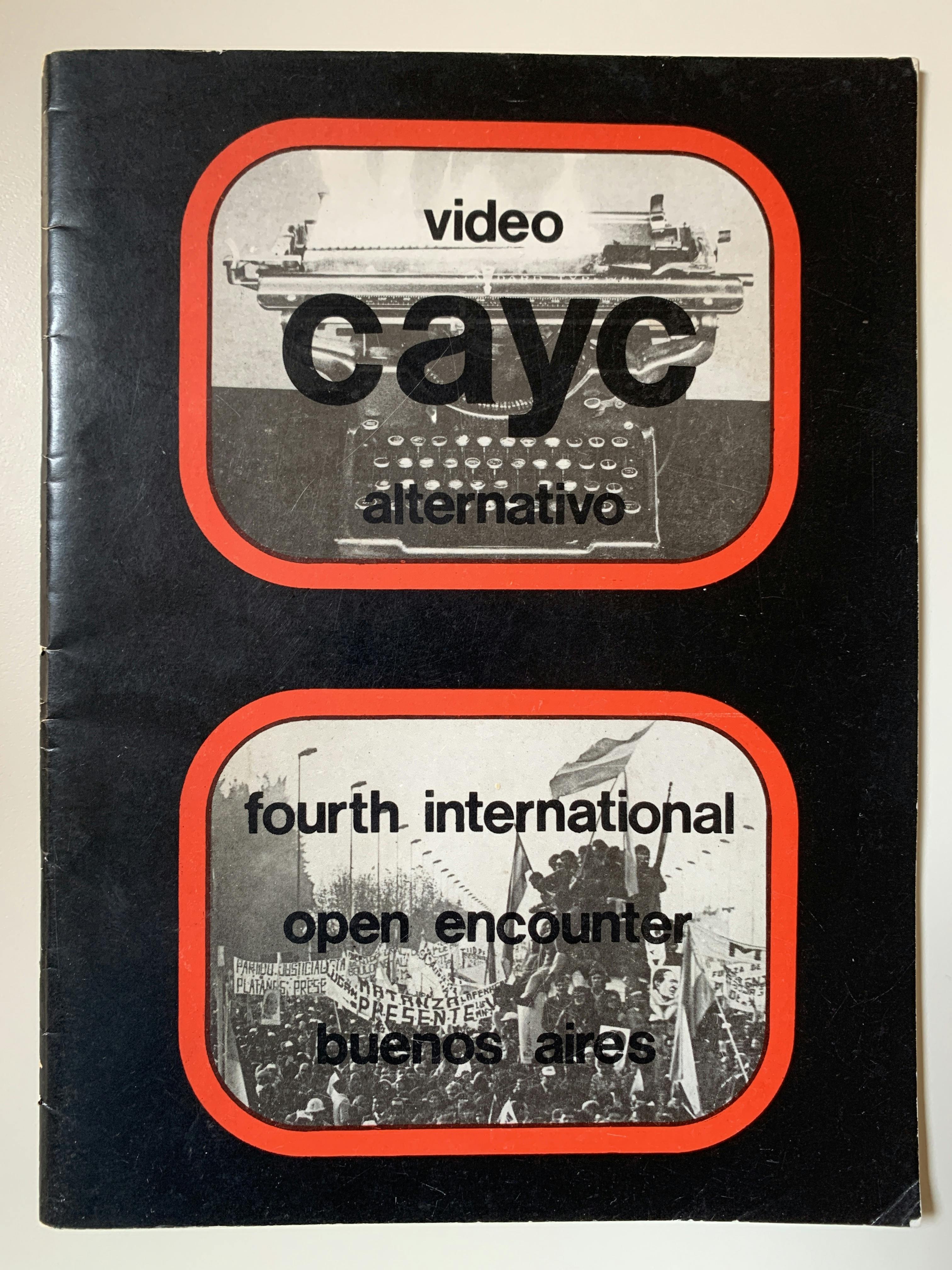

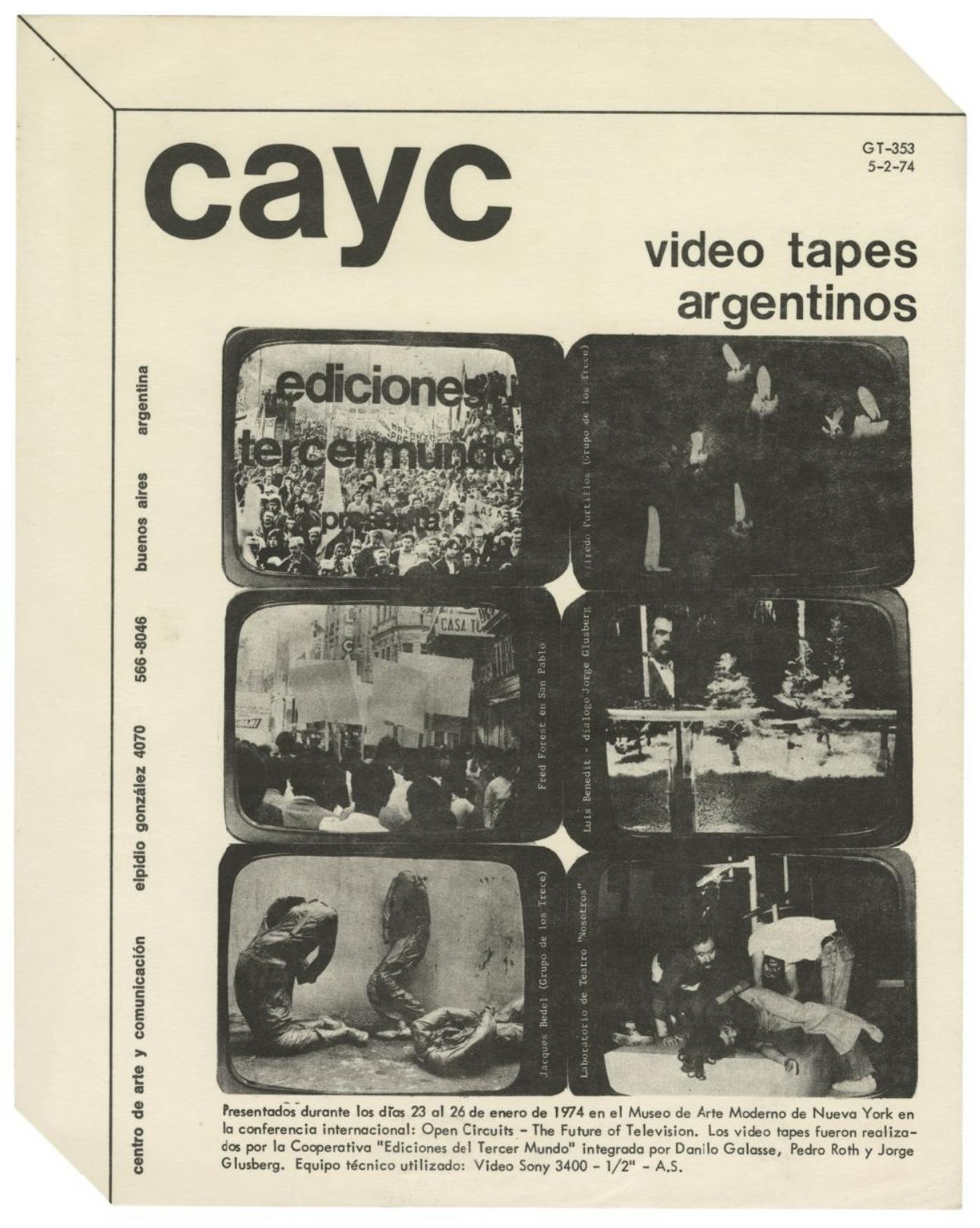

Founded in Buenos Aires in 1968, the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC) grew over the ensuing decade to become one of the most prominent promoters of experimental art in the Latin American region during the late twentieth century (fig. 1). Among the most significant forms of experimentation the institution fostered during its intensive first decade of activity was with audiovisual technology. Organizing a wide array of exhibitions and other programs focused on artistic uses of such technologies throughout the 1970s, the CAYC also purchased film and video equipment that it then made available to the group of Latin American artists closely associated with it, thus positioning itself as a type of laboratory space for production in new and time-based media (figs. 2–3). 1 And yet today, some thirty odd years after the Centro’s eventual dissolution, these audiovisual experiments present an archival and, by extension, interpretive conundrum for scholars: largely lost or destroyed, the many tapes, films, and other electronic media the Centro and its associated artists produced survive today mostly through various forms of secondary documentation such as photographs and paper records (figs. 4–5). Analyzing these works thus often consists in the paradoxical and frustrating experience of viewing experiments in new media only as they have been mediated through other, older media.

The recent acquisition by the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) of several previously unknown audiovisual works created at the Centro during the institution’s first decade presents an exciting opportunity to shift this interpretive landscape, offering as it does a rare, direct view of the works themselves, before and apart from their documentation. However, as this essay will suggest, the view these newly recuperated works provide is anything but unmediated. Indeed, a close look at the audiovisual materials in the Centro de Arte y Comunicación Archive, housed in the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives, reveals these works to be deeply preoccupied with their own mediation—with the multiplications, transformations, and contortions of their content and form that resulted from their combinations of moving image technologies with other distinct material supports. Drawing on the notion of intermedia—a term the CAYC itself frequently employed in its own discursive output—this short essay will consider how the institution’s audiovisual experiments emphatically span the space between media, and how this spanning can shed light on the CAYC’s own institutional self-fashioning and on the methodological and archival politics of studying it today. 2

The acquisition by ISLAA of several previously unknown audiovisual works created at the CAYC presents an exciting opportunity to shift the interpretive landscape, offering as it does a rare, direct view of the works themselves, before and apart from their documentation.

Aptly titled From Leonardo to the Intermedia Revolution, a video created at the CAYC in 1980 provides a useful entry point for approaching the institution’s engagement with the concept of intermedia (figs. 6–8). Produced at the close of the CAYC’s first decade, the tape marks a moment of transition in the institution’s history, as in the 1980s, the CAYC would subsequently turn away from the visual arts to focus more exclusively on architecture and design. As such, the video stands as a historical bookend to the CAYC’s most ambitious period of artistic experimentation in audiovisual media. Moreover, the tape’s structure and content exemplify many of the peculiarities of that experimentation, and it may thus serve as a framing device for the CAYC’s corpus of new media more broadly. Originally created for a symposium on intermedia artforms hosted at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in February of 1980, the tape is not a work of art per se but rather a type of didactic piece of art criticism elaborated on video—what we might call an audiovisual essay. 3 This unique genre of the audiovisual essay occupies a large proportion of the film and video output generated by the CAYC, in many ways eclipsing the experiments that artists produced using the institution’s audiovisual equipment. 4 In other words, if audiovisual technology had functioned at the CAYC as an impetus for artistic exploration, what the genre of the audiovisual essay demonstrates is that, from the very start, this technology had also figured as an institutional instrument for art’s mediation. In what follows, then, the present essay will offer a close formal reading of several key examples of this genre in ISLAA’s collection, considering how these works critically mediated the artistic output the CAYC facilitated and promoted.

The tape the CAYC screened at the Guggenheim consists of a tract written by Jorge Glusberg, the CAYC’s founding director and controversial spokesperson, read aloud in English by an unseen narrator. 5 Delivering a highly theoretical, structuralist-inflected account of the phenomenon of intermedia, the spoken narration unfolds in tandem with a rolling sequence of still images, interspersed with frames of text that offer their own, parallel narration of intermedia’s historical genealogy, which they trace from Leonardo da Vinci to Marcel Duchamp and up to the CAYC’s own exhibition Argentina Inter-Medios, staged in Buenos Aires in 1969. In a key moment early in the tape, the narrator takes aim at the preoccupation with medium specificity characteristic of modernist criticism, declaring that “it is inconceivable for art to retain an artificial purity,” a statement he utters as images of Leonardo’s mechanical inventions flit by. 6 As an antidote to such doctrinaire modernist purism, and as a contemporary vindication of Leonardo’s transdisciplinary designs, the narrator later describes how current “intermedia postulate themselves as a full-scale revolution in art, an art of interweavings between man and machine, light and the movement of the body,” a declaration spoken while still images of Duchamp’s own mechanical devices cycle across the screen. The tape ends with a sequence of images documenting recent works by Argentine artists closely associated with the CAYC, including Luis Benedit and Víctor Grippo, whose environments involving electronic machinery, plants, animals, and human participation neatly instantiate the “interweavings” between the mechanical and the biological that the tape’s narrator trumpets. In this way, the CAYC’s audiovisual essay sought to situate the institution as the inheritor of a prestigious, transhistorical lineage of intermedia, a practice of inventive combinations between art and machine of which the Centro and its associated artists would be the paradigmatic contemporary exemplars.

The unique genre of the audiovisual essay occupies a large proportion of the film and video output generated by the CAYC, in many ways eclipsing the experiments that artists produced using the institution’s audiovisual equipment.

The theory of intermedia described by the textual and spoken narration in the CAYC’s video is fairly straightforward, if idiosyncratic, consisting essentially of a practice that would combine aesthetic expression with contemporary technology in an apparent dialogue between art and science. Yet the formal aspects of the CAYC’s tape offer their own, distinct conception of intermedia, one that is both more literal and more complex. For the tape’s elements effectively coordinate a concrete interface or encounter between distinct mediums, resulting in a layering of mediations that confuse the hierarchies between representation and referent. The narration itself, for example, emerges from an “interweaving,” to use Glusberg’s term, of written text, spoken word, and visual image that troubles any stable relationship that might exist between them: it is never possible to determine which of these three registers, if any, is meant to take dominance, and which are meant to play the subsidiary roles of illustration, demonstration, or counterpoint. Meanwhile, the visual content of the video, in turn, stages a similar interweaving, this time between material substrates. The images of works of art that cycle across the screen are, after all, not video recordings of those works but rather video recordings of photographs of those works, a fact made evident both by the still nature of the images, and by an explanation in the video’s credits that cites the photos’ authors. Flitting across the screen in regular sequence, these static images produce the bizarre effect of a taped slideshow, thereby occupying the durational dimension of video’s time-based property while at once obviating video’s status as a moving image. In the case of the works by Argentine artists that appear at the end of the tape, this encounter between video and photography furthermore produces an ironic documentary doubling. Rather than simply documenting the work of its associated artists, the CAYC’s video documents that work’s documentation. Mediation itself, in a crucial respect, thus becomes the subject of the video’s recording.

It is significant that the CAYC should choose video as the medium for its most extended institutional reflections on the phenomenon of intermedia. Video had in fact played an outsized role at the Centro throughout the 1970s, serving as one of the central pillars of the institution’s programming and promotion throughout the decade. In addition to inviting its associated artists to experiment and produce works with the video equipment it had purchased, the CAYC also created its own production company, Ediciones Tercer Mundo (Third World Editions), through which it created various didactic and promotional tapes, including its various audiovisual essays. Furthermore, and most importantly, the institution organized a groundbreaking series of international symposia on video hosted in various cities across Latin America, Europe, and Japan, for which it sought to bring together and spark dialogue among artists working in the medium from across the globe. 7

Video had played an outsized role at the CAYC throughout the 1970s, serving as one of the central pillars of the institution’s programming and promotion throughout the decade.

Indeed, so important was video to the institution’s project that the CAYC devoted an entire audiovisual essay to the medium, a work which, fittingly enough, was itself produced on video. Titled Retórica del arte y la tecnología en Latinoamérica (Rhetoric of Art and Technology in Latin America), and likely created around the same time as the CAYC’s essay for the Guggenheim discussed above, the CAYC’s video about video follows the same basic format as the Guggenheim tape, with the camera panning over still photographic images of works produced by CAYC artists as an offscreen narrator reads aloud from a densely theoretical text analyzing the phenomenon of video, this time in Spanish. The narrator’s script, drawn from a book Glusberg had published in 1978, describes Latin American video art as animated by two contradictory tendencies. 8 On the one hand, the narrator explains midway through the tape, “the fundamental determination in video’s rhetoric is the technical process through which it produces its images.” As such, video art presents a meditation on its own “technical conditions of production,” what the narrator calls a “rhetorical game” in which video constantly refers to its own technical properties and affordances. In contrast to these formalist games of self-reference, however, Latin American video is simultaneously animated by a contrary thrust, the narrator argues, one that tends to locate it within its geopolitical and social context. As the offscreen voice explains, the political crises faced by “underdeveloped” countries such as those in Latin America necessitates that art produced in such contexts constantly operate as a “thematization of its socio-contextual conditions of production.” In the case of video, the medium becomes a “testimonial” of political struggle.

This last point is crucial for understanding how video fit within the CAYC’s broader project during the institution’s first decade. Throughout the 1970s, Glusberg had been at the forefront of a vociferous group of critics, curators, and theorists who had begun to insist on the inherently political nature of Latin American art, a characteristic they believed distinguished that art from dominant trends in the Global North. 9 Indeed, as the CAYC director would write for the catalogue of what was perhaps the institution’s most important and highly visible exhibition of the decade, Art Systems in Latin America, “The Europeans make theoretical discussions of political problems, [while] the Latin Americans necessarily include them in their works since they live these political problems daily.” 10 Video, conceptualized as a “thematization of its socio-contextual conditions of production,” would thus serve as a quintessential instance of precisely this type of lived daily politics, exemplifying Latin American art’s apparently organic, distinguishing politicization.

Fig. 9: Jorge Glusberg, dir., Retórica del arte y la tecnología en latinoamérica, ca. 1980 (stills). U-matic video, color, sound, 23.39 mins. Frames showing works by Mirta Dermisache, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, and Alfredo Portillos. Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC) Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. Copyright Matías Glusberg

Fig. 9: Jorge Glusberg, dir., Retórica del arte y la tecnología en latinoamérica, ca. 1980 (stills). U-matic video, color, sound, 23.39 mins. Frames showing works by Mirta Dermisache, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, and Alfredo Portillos. Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC) Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. Copyright Matías Glusberg

Throughout the 1970s, Glusberg had been at the forefront of a vociferous group of critics, curators, and theorists who had begun to insist on the inherently political nature of Latin American art, a characteristic they believed distinguished that art from dominant trends in the Global North.

The irony of the CAYC’s Retórica tape is that, while it declares political context as the subject of Latin American video, it makes this context effectively invisible within its own content (figs. 9–11). For if anything, the photographic snapshots that pan across the video’s screen in fact decontextualize the works they represent, obscuring their respective situations within specific moments and spaces as they convert those works into a sequence of homogeneous and interchangeable images. “Politics” becomes a vacant concept within the CAYC’s video about video, and this dynamic mirrors the ironic status within the tape of the concept of video itself. Of the dozens of works by CAYC artists whose photographic documentation pans across the screen, none are in fact works of video art. As the tape’s narrator discourses on the singularity of video art and its politicized uses in Latin America, photographs of non-video-based works cycle by, with sculptures, paintings, installations, and various performance- and conceptual-based interventions appearing in regular succession. Far from offering a view of Latin American video art that the tape’s narration seems to promise, then, the CAYC’s tape effectively evacuates video as a subject, substituting it with other artistic mediums whose photographic registration comes to fill the screen. Within the intermedial space of the CAYC’s Retórica video, the concept of video itself, and the concept of politics with which it is imbricated, each become what we might call a floating signifier, a type of empty conceptual shell into which various referents step to fill the void.

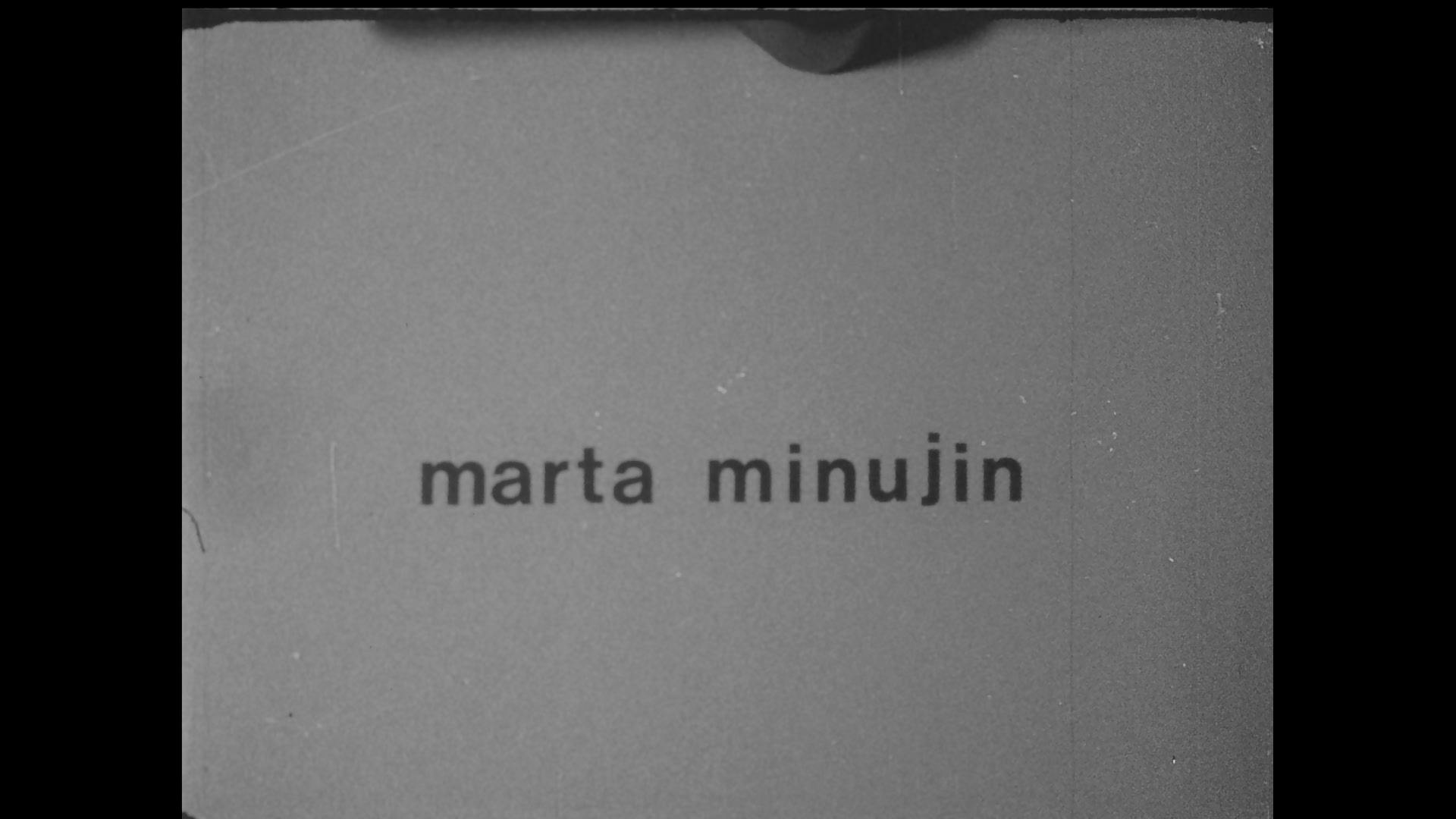

These intermedial ironies reach their height with a segment near the end of the video that shows images of Argentine artist Marta Minujín enacting her 1969 project Minuphone (fig. 12). In one photograph of the project that appears on the video’s screen, an unidentified man stands to Minujín’s left, recording the artist with a film camera as she manipulates the door of the phone booth that is Minuphone’s central prop. Capturing this scene of audiovisual capture, the CAYC’s video essay thus effectively stacks three distinct mediums—video, photography, and film—atop one another, thereby configuring a tense correlation between two distinct moving image technologies that appear tethered together, as it were, by photography’s still frame. In so doing, the CAYC’s tape summons the context within which video technology emerged as a new medium during the 1970s. Video had first appeared late in the previous decade as a radical alternative to the older medium of film, which had, until that point, been the only existing technology capable of producing moving audiovisual images. With long production and development timescales and restrictive projection constraints, film carried with it specific temporalities and viewing conditions. Video, however, seemed to circumvent these limitations through its novel capacity for instant, long-distance transmission in various scales and formats. Over the ensuing decade, artists and activists across the globe would seize upon these new affordances as motors for various utopian and critical counterspaces through which they sought to subvert contemporary commercial media. 11 Indeed, the CAYC itself framed its own video initiatives in precisely this way, often casting the networks of video exhibition and exchange that it endeavored to foster as a type of politicized “alternative television” that would run counter to the vectors and flows of dominant media then emanating from the Global North. 12 And yet, in contrast to this early discourse that heralded video as superseding and opposing film, the brief appearance of the film camera in the CAYC’s video about video suggests a different relationship between these two audiovisual technologies, one based not on opposition but rather on embeddedness, correlation, and mutual reflection.

Fig. 13: Jorge Glusberg, dir., Glusberg y Benedit, 1973 (stills). 16mm film, black-and-white, sound, 7:32 mins. Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC) Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. Copyright Matías Glusberg

Fig. 14: Jorge Glusberg, dir., Glusberg y Benedit, 1973 (stills). 16mm film, black-and-white, sound, 7:32 mins. Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC) Archive, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. Copyright Matías Glusberg

The CAYC often casted the networks of video exhibition and exchange that it endeavored to foster as a type of politicized “alternative television” that would run counter to the vectors and flows of dominant media then emanating from the Global North.

The CAYC’s own archival materials bear out this type of correlational or reciprocal intermediality between video and film (figs. 13-15). For film itself, while less cutting-edge and thus much less publicized by the CAYC, was nevertheless a crucial instrument for the institution’s self-promotion during the 1970s, and it is ironically through film that we gain some of our greatest insights into how the institution and its associated artists used video. Such insights are conveyed through a series of short black-and-white 16mm films the CAYC produced in 1973 for an international workshop on experimental art hosted in Berlin that year. Serving as promotional materials meant to publicize the institution’s activities, these works share the same basic structure as the audiovisual essays on video discussed above, figuring not as works of art per se, but rather as pieces of institutional discourse describing works of art produced under the CAYC’s auspices. In one film, titled Glusberg y Benedit, the CAYC director is recorded with the artist Luis Benedit as the pair tours the institution’s Buenos Aires gallery space, where they descend into the basement to view Benedit’s Phytotron (1972) as it had been installed there. The film is remarkable for the detail with which it shows the extensive array of video equipment the CAYC boasted already at that early date, with the film camera pausing at various junctures to record several television monitors screening closed-circuit video loops throughout the space. The film captures the sense of a vibrant, stimulating laboratory of video production, the very context in which the CAYC’s artists would have produced their video works. Although almost none of those works survive today, we glimpse the apparatus that made them through the filter of another, older machine that video was purported to have surpassed.

And we even gain glimpses of some of these lost video works themselves through that same filmic filter (figs. 16-17). Another short film created for the Berlin workshop, titled simply Latin American Artists, offers vignettes showing the works of various CAYC-associated artists slated to participate in the event. One of the vignettes, dedicated to Marta Minujín, shows a brief shot of an unidentified video work by the artist being screened on a monitor, with the artist’s face looking out from the frame of the monitor to stare straight into the camera. The film thus produces a doubling of cameras that correlates video and film: while Minujín would have recorded herself looking into a video camera when she produced her work, in her second recording of the work, made for the purpose of promotion and dissemination, that camera is replaced by a film camera into which the artist effectively peers. An intermedial reverberation thereby emerges between the representations of Minujín’s works in this film and in the Retórica video discussed earlier. The Retórica tape supplies the precise inverse to the CAYC’s 1973 film recording of Minujín’s video, that is, a video recording of a scene of filming. In this way, video and film appear constitutively embedded within each other, correlated with each other across an intermedial field of audiovisual production. In stark contrast to the prevailing discourse of the 1970s that celebrated the radical break with film that video’s novel technological affordances promised, at the CAYC video appears perpetually haunted by its technological predecessor, which emerges as both its content and its frame.

The intermedial dynamics that this essay has tracked can ultimately help us reconceptualize key questions of archive and politics that frame the CAYC’s production during its first decade and that stand as central concerns for scholars today. The audiovisual materials in ISLAA’s collection do not, in fact, show us much about how CAYC artists used film and video; that question largely remains as foggy as ever. Rather, these materials demonstrate how the CAYC’s own institutional use of audiovisual technology was bound up in an intermedial network of exchanges between different supports. Within this network, works of art transited between one substrate and another, creating paradoxical, even contradictory doublings and layerings. These dynamics force us to revise straightforward notions of the archive as simply documentary—as an apparatus that dutifully records past events through various media of registration. As the CAYC films and videos at ISLAA demonstrate, what appears represented in the content of one documentary medium is often yet another documentary medium, whose own content, in turn, documents still further processes of documentation. Rather than clearly representing past events and objects, then, these media represent the contingent, shifting technologies and materials of representation itself, revealing its infinite mediation as it spans different media. Finally, this process can thus offer a timely lesson for understanding the CAYC’s politics. While Glusberg sought to characterize the CAYC as a politicized counterpoint to European and US trends, the institution’s audiovisual materials show the challenges of representing politics. Indeed, these materials remind us to stay alive to the ways in which politics, like art, can become an abstracted image, rather than a concrete process, as it is looped, repeated, and remediated through the intermedial circuits of the CAYC’s promotional apparatus.