Re: Collection invites a range of historians, curators, and artists to respond to the artworks in our collection through approachable texts.

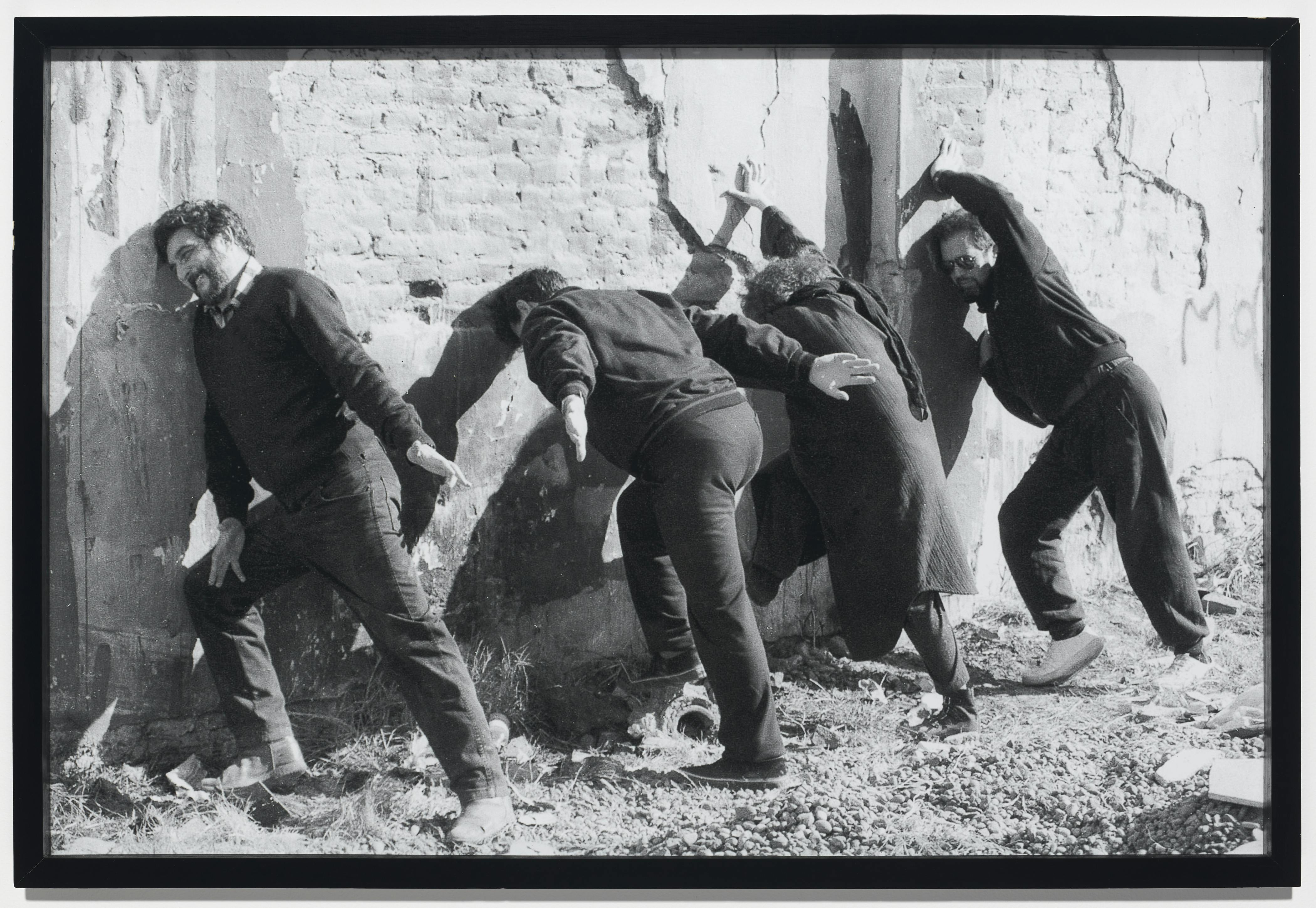

Grupo Escombros, Teoría del arte (Theory of Art), from the series Pancartas (Placards), 1988, printed 2018. Ed. 1/3. Laser print, 15 5/8 × 23 1/2 in. (39.7 × 59.7 cm). © the artists. Photo: Arturo Sánchez

Imagine the following scenario: a group of four individuals, clad in black, use their hands, shoulders, and heads to exert pressure on a masonry wall, contorting their bodies into configurations that resemble load-bearing support braces. Their bodies’ diminutive sizes in relation to that of the flat barrier before them suggests that their task is Sisyphean, without visible impact on the wall that effortlessly resists their weight. It’s unclear whether their intention is to demolish the wall or to prevent it from collapsing upon them. Nevertheless, they appear united in their purpose, organized around a common goal that, though ambiguous to the observer, constitutes them as a coordinated entity—a group.

What is a group? For the British psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion, twelve strangers on a beach do not necessarily make a group. “But if someone in the water cries for help and the twelve individuals respond by trying to save the swimmer from drowning in some kind of concerted action, however rudimentary the concertedness may be, they have become a group in that they now have a function.” 1 According to Bion, a group is formed through a shared purpose, however durable or fleeting that might be. “This may last for only a few minutes or it may turn into an organization of life savers which goes on for years.” 2 For Bion, not only is a group’s task essential to its constitution, but it is also what ensures the group’s survival. In the scenario previously described of four individuals encountering an obstacle that both directs and impedes their free movement, their action of bracing or destroying, of exerting the weight of their bodies upon the wall in front of them, constitutes them as a group. A photograph—documentation of an action performed by the Argentine collective Grupo Escombros in 1988—not only testifies to the group’s existence but in some ways ensures its continuation.

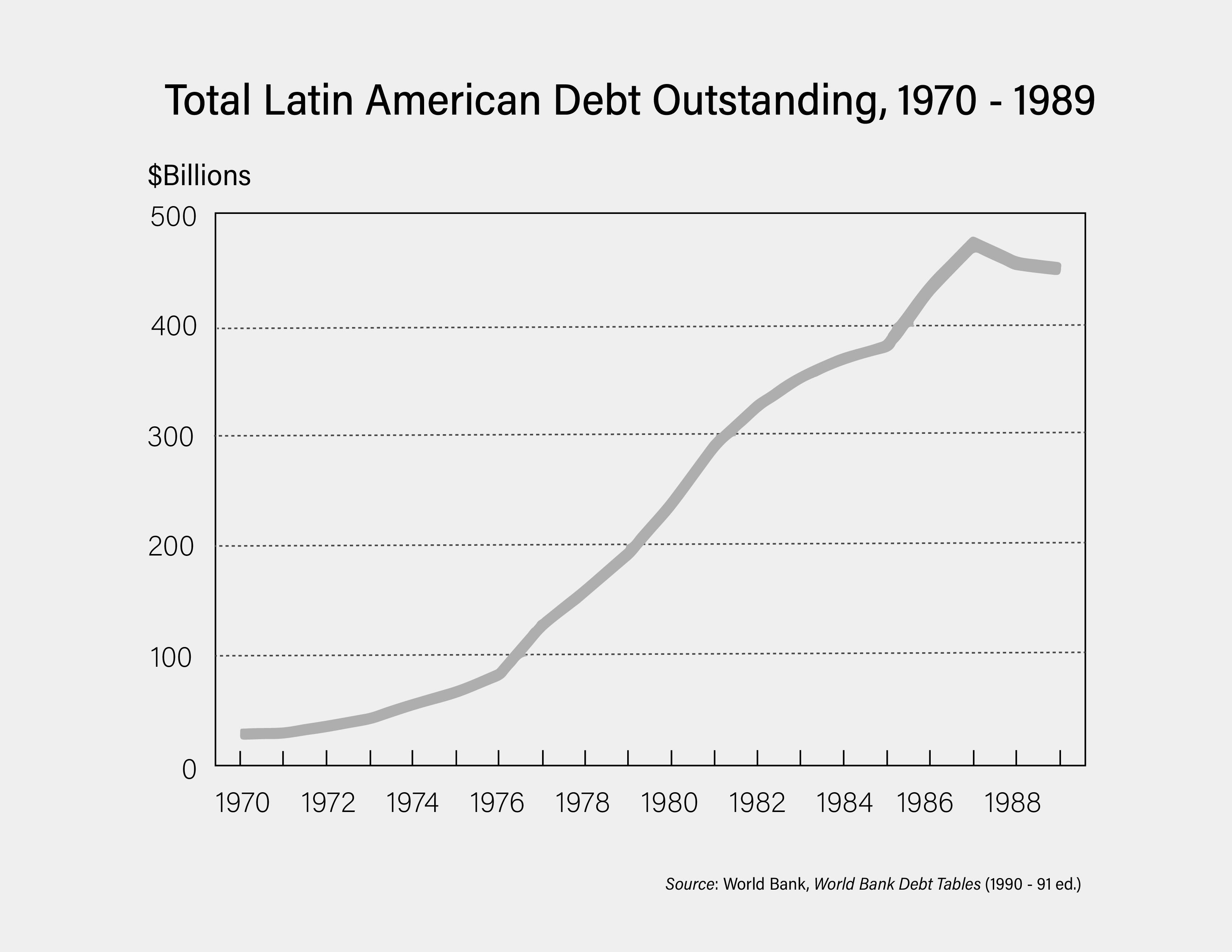

Walls and other more abstract boundaries, both removed and constructed, abounded in Latin America in the 1980s, a period in which trade barriers were lifted and public resources enclosed by authoritative administrations. Often referred to as “La Década Perdida” (The Lost Decade), this period has been historicized as one marked by state terrorism, hyperinflation, and extreme national debt. Triggered by shocks in crude oil costs, rising interest rates, and predatory lending from US commercial banks, Latin American countries were left drowning in so-called “Third World debt” totaling more than $327 billion.

Total Latin American debt outstanding, 1970–1989.

The privatization of public enterprises and flooding of international trade markets—a familiar script of uneven development—simultaneously created a drought of opportunities at the local level. Indeed, Latin America’s Lost Decade is what undergirded what was, for the US, a period in which consumerism was promoted as an “American” democratic ideal at the end of the Cold War. Theorists such as Argentine semiotician Walter Mignolo have long argued that these entwined relations of economic expansion and contraction—the fact that a boom in one part of the world relies on a bust in another—perpetuate the ongoing legacy of colonialism. As the global economy continues to weigh heaviest on the most dispossessed, new questions arise about how shifts in the distribution of this burden are sensed or felt. How do we observe the redistribution of surplus and debt?

Constituted within this precarious context, Grupo Escombros worked primarily in performance and photography, activating civic space in La Plata, the capital of the province of Buenos Aires. The group was formed by Horacio D’Alessandro, David Edwards, Héctor Ochoa, Héctor Puppo, Luis Pazos, and Juan Carlos Romero at a moment when survival was not only an economic reality but also a social one. From 1976 to 1983, the Argentine government’s military junta disappeared (largely by execution) thirty thousand citizens believed to be communists and socialists. Escombros’s work not only developed out of this context but also sought to navigate the weight of this violent and traumatic recent history, responding to ways this not-so-distant past lingered in what Argentine political scientist Guillermo O’Donnell calls the “bureaucratic authoritarian state.” For O’Donnell, such governance furthers strategies of capitalist expansion while exacerbating existing inequality, guaranteeing “domination exercised through a class structure subordinated to the upper fractions of a highly oligopolized and transnationalized bourgeoisie” and does so through “a set of organizations in which specialists in coercion have decisive weight.” 3 Bureaucratic authoritarianism thus authorizes particular actors and groups to act on behalf of the state, often by disempowering, or walling out, the masses. O’Donnell describes this as a division between the estado and the pueblo, wherein the latter is systematically weighed down by the hegemonic policies designed to sustain the former. Throughout their work, Escombros agitated these tensions as a form of civic service, making work for and alongside the people of La Plata.

In Grupo Escombros’s 1989 manifesto La estética de lo roto, they advocate for a Lefebvrian right to the city, writing, “the site where our works gain concretion is the street.” 4 Like many Latin American cities, public spaces were central to the design of La Plata, which served as the group’s base. The Argentine urbanist Pedro Benoit designed the city as a square grid with diagonal boulevards radiating from its central axis, not unlike Haussmann’s plan for Paris, and punctuated by a series of plazas and parks. Yet, rather than activate these predetermined sites of civic life, Escombros intervened beneath highways and in abandoned quarries, using the city’s arteries, margins, and undeveloped spaces as a medium of dissent. For Escombros, the city was a kind of social commons. As stated in their manifesto, “We are on the street because our friends make it possible.” 5

The group situated its work against oppressive models of conformity and compliance enacted by state power. They operated as an open system with a non-hierarchical leadership structure and permeable boundaries, writing, “We are an open and horizontal group. The number of our members is not fixed and has no limits. We all, without exception, have a right to voice our opinion and make decisions. . . We uphold solidarity as the highest value.” 6 Escombros embodied what US theorist Emily Apter might call ethical militance —a “political collectivity that seeks to supplant bourgeois individualism with a new notion of the group or ontological set.” 7 Escombros functioned as a proposal for a new paradigm or counter-ideology that could be adopted by anyone—to turn the individuals on the beach into a group, urgently trying to save everyone in sight from drowning.

Santiago Sierra, Muro de una galería arrancado, inclinado a 60 grados del suelo y sostenido por 5 personas (A Gallery Wall Torn out, Inclined at 60 Degrees from the Floor, and Held up by Five People), 2000. © 2022 Santiago Sierra / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid. Photo courtesy the artist and Labor, Mexico City

Indeed, the weight of the 1980s debt crisis influenced the shape of Latin American economic and social policy for decades. Neoliberal restructuring and reforms enclosed common land and public enterprises, as countries such as Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil opened their borders to foreign investment. Bolstered by authoritarian governments and special interest groups, these adjustments dismantled unions and eroded social bonds. Situated within these complexities, in the year 2000, the Spanish artist Santiago Sierra paid five Mexican workers to extract and support a sheetrock wall at a sixty-degree angle for four hours a day over the course of five days. Sierra’s protocol enlisted the labor of a demographic willing to take on this work—at 65.5 pesos per hour ($3.25)—illuminating the post-NAFTA economy that made such wages standard. In the documentation of Sierra’s action, the five men have become architectonic units. Their task is symbolic, manual, and dehumanizing—turning their bodies into scaffolding for the sheets of drywall that rest upon their hands and backs.

Sierra’s work bears striking visual similarity to that of Grupo Escombros, and both offer analogous social critiques. The conditions that constitute each of these works are, in fact, braided through the afterglow and enduring impact of a lost decade. While Grupo Escombros exerts pressure against the masonry wall, Sierra’s workers labor to keep it at a precise position. Through this arduous task, Sierra questions contemporary art’s maintenance, infrastructure, and the exploitative economies in which it is suspended. If Sierra’s interior wall resides within the institutionalized spaces of art, Escombros’s exterior wall is its public-facing surface, a Teoría del arte (Theory of Art) that suggests art’s perceived impenetrability as well as a provocation of what it can do. Escombros’s work is suggestive of the formation of groups in relation to the walls that enshrine the wealth and power of O’Donnell’s “transnationalized bourgeoisie.” The collective’s amorphous social system bears resemblances to other theories of the collective that had largely been excluded from economic and political life (such as Hardt and Negri’s “multitude”) despite the ways in which the global economy relied on the perpetuation of their labor and indebtedness. Clad in black, the members of Grupo Escombros are figures of mourning, ghosts, even, of the lives that haunt the civic infrastructure of the contemporary Argentine state. Amidst increasing authoritarianism, systematic inequality, and environmental slow violence, in 2022 inflation rates are the highest they’ve been since 1981. These truths are like a shadow of the past, which, for some, weighs like a nightmare on the present. What endures and what remains in the wake of structural collapse? If a group’s primary task is to preserve itself, then Grupo Escombros reminds us that for large groups like societies, “There is only one possible cultural project: survival.” 8

It has not been possible to locate the copyright holders of the header image, despite having carried out a diligent search. ISLAA makes itself available to rights holders to agree on the content of the legal notice.