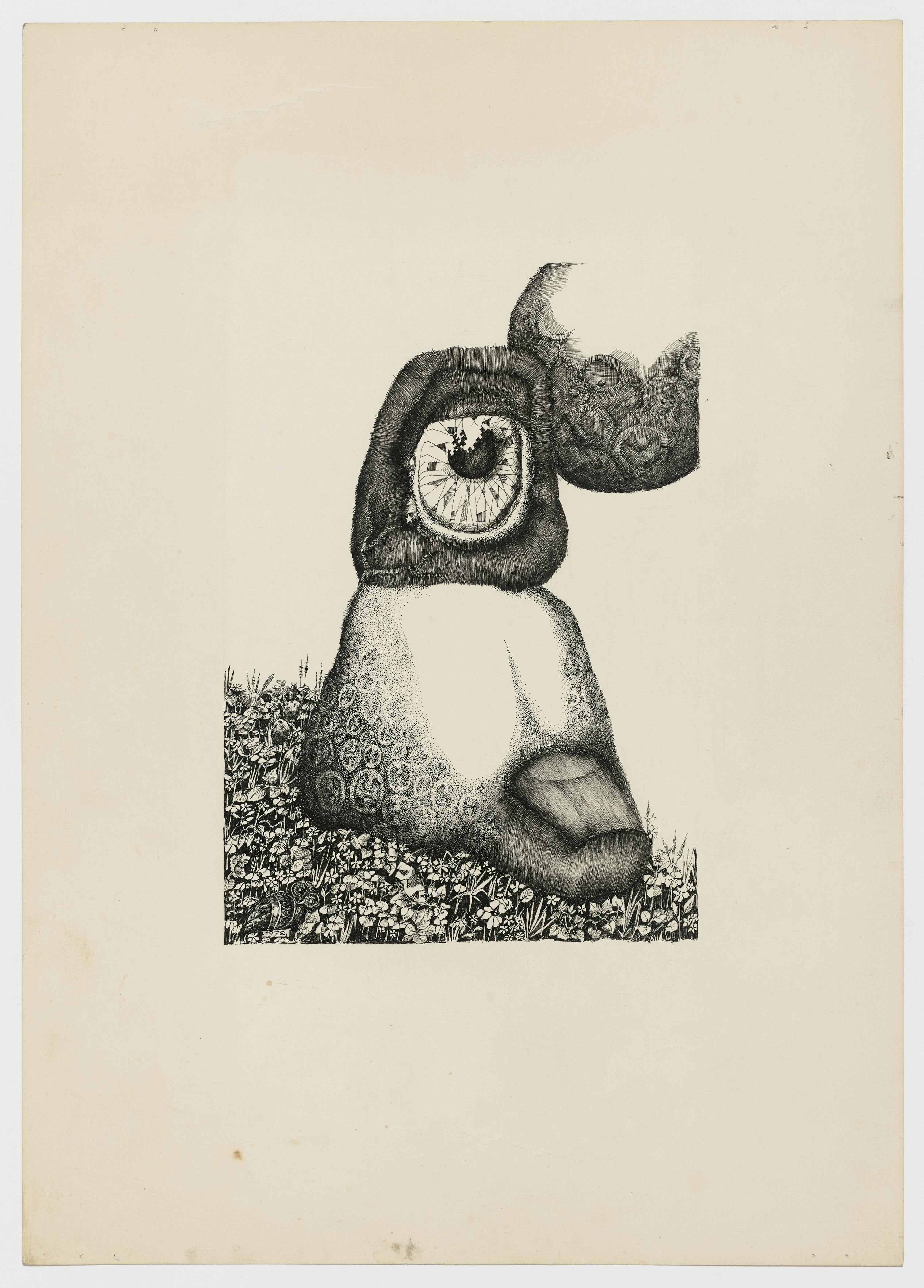

Beatriz Battione, Untitled, 1972. Ink on paper, 23 5/8 × 19 5/16 in. (60 × 49 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

The Writer in Residence series offers scholars the opportunity to conduct research on Latin American art through materials in the ISLAA Library and Archives.

In Spanish, the suffix “–azo” or “–aza” has multiple meanings: it can function as an augmentative (a big dog is a perrazo), and it can convey either a derogatory or appreciative sense (the latter is frequently applied in the realm of football, where remarkable goals are golazos). It can also carry an emotional connotation, such as when describing an exceptional mother as a madraza. This suffix can sometimes indicates a forceful impact, as in almohadillazo (a strike performed with a cushion). However, in the case of dibujazo, which stems from the term dibujo (drawing), we cannot trace a genealogy that gives it a single meaning. Since the 1970s, this composite word, accompanied by its article, has come to represent a brief but influential epoch within the visual arts in Uruguay. The “El Dibujazo” Collection, housed at the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), comprises 108 drawings that constitute an important portion of the artworks created by this group. The collection contains drawings primarily produced between 1965 and 1975 by more than thirty artists, with Alberto Schunk and Álvaro Armesto featuring prominently.

Although the name “El Dibujazo” is universally attributed to the critic María Luisa Torrens, who made it public for the first time in December of 1972 when describing this artistic movement in an annual review for the Uruguayan newspaper El País, 1 the term had been widely in use since 1969 in tertulias and cafés, particularly around Galería U in Montevideo. 2 Indeed, the term cannot be traced back to a single person. According to curator Manuel Neves, for artist Jorge Paéz the denomination was associated with scale, given that his drawings were mural size. 3 Conversely, Domingo Ferreira posits that the suffix shares an affinity with the Cordobazo, a workers’ insurrection that took place in Cordoba, Argentina, in May 1969. 4 Twenty years later, a similar social resistance in Caracas adopted the same suffix: Caracazo.

When Torrens proclaimed the emergence of El Dibujazo, she refrained from assigning a specific meaning to it. In 1972, this appellation played a crucial role in promoting and spreading the work of artists associated with this movement, serving as its formal catalyst. Fifty years later, this term can instead be interpreted as a porous multiplicity. Its blurry origin is, first and foremost, collective. Whether the addition of “-azo” was meant to convey largeness, greatness, an affective overtone, metaphorical impact, political alliances or, most likely, a combination of all these aspects, the aim of my etymological meandering here is to explore El Dibujazo from a position of confluence rather than congruence.

El Dibujazo was loosely constituted by young, mostly amateur Uruguayan artists working primarily in the medium of drawing between the late 1960s and early 70s.

El Dibujazo was loosely constituted by young, mostly amateur Uruguayan artists working between the late 1960s and early 70s primarily in the medium of drawing—although some integrated engraving, and, in the case of Sara Pérez, photocopies—with a strong inclination toward black-and-white representation which Celmar Poumé, Alberto Schunk, Nelson Avdalov, Jaime Pares, and others eventually subverted by integrating color. However, the variations and distinctions within El Dibujazo are wide: Néstor Canessa’s cumulative and suggestive lines, the dark hyperrealism of Jorge Satut, Eugenio Darnet’s zoomorphic monsters, the Pop art of Ruisdael Suárez, and Beatriz Battione’s laberyinthical spaces, among many others, contribute to its diverse landscape. Artist Domingo Ferreira characterized this tension between heterogeneity and commonality as a “culture of alluvium”: in other words, although there was a shared sense of direction, it encompassed a great deal of variety. 5

The stakes against which this generation emerged were high. In a July 1972 interview, artist Jorge Satut declared, “El arte, ahora, es vivir la realidad, o nada” (Art now means either living in reality, or nothing), signaling the inseparability of life and art. 6 Amid the unsettling social and political scene that had been brewing in Uruguay since 1968, artistic production took a drastic turn toward the medium of drawing. This technique offered a more direct form of expression at a time when artists desired to capture the moment, rebel against oppression, and critique it through the use of both humor and horror. Tools like the rapido-graph, dry-pen, and other inks became instrumental in circumventing long and time-consuming processes, as their marks on the page were immediate. The adoption of these instruments, not as auxiliary but as the central means of representation, facilitated a certain departure from traditional artistic tools (easel, brushes, canvases, oils, palette, knives, etc.), bringing artists closer to more popular forms of representation. Artists associated with El Dibujazo freely borrowed from the aesthetics of comics, cartoons, advertising, and graphic design; indeed, some draftsmen concurrently worked as illustrators in newspapers and publishing houses, as exemplified by Domingo Ferreira, Fernando Álvarez Cozzi, and Carlos Pieri. The accessibility and affordability of these mediums might have also played a role in the rapid expansion of this practice among the youth, amateurs and professionals alike.

The manifestation of societal and political conditions through creative practice during this period was not confined to the visual arts. The purpose of this essay is to explore how the escalating erosion of democracy, the constraining freedom of expression, and the rising instances of violence and surveillance influenced contemporary literature at the time as well. How do the drawings produced in that period overlap with writing that emerged simultaneously? How were Uruguayan writers grappling with, rebelling against, and resisting their uncomfortable reality? Could the convergence of anxieties across lines and words provide a reading more attuned to the atmosphere from which they emerge? The desire to ask these questions comes partly from anthropologist Kathleen Stewart’s notion of atmosphere. According to Stewart, “atmosphere is not an inert context but a force field in which people find themselves.” This understanding of atmosphere allows context and lived experience to coexist, to shape one another. Atmosphere has the capacity to contain multitudes, register varied levels of intensity, and blur distinctions. Therefore, approaching El Dibujazo as an atmosphere welcomes the lived experience of artists and writers as inseparable and focuses on the intensities that derived from their lived experiences across disciplinary boundaries.

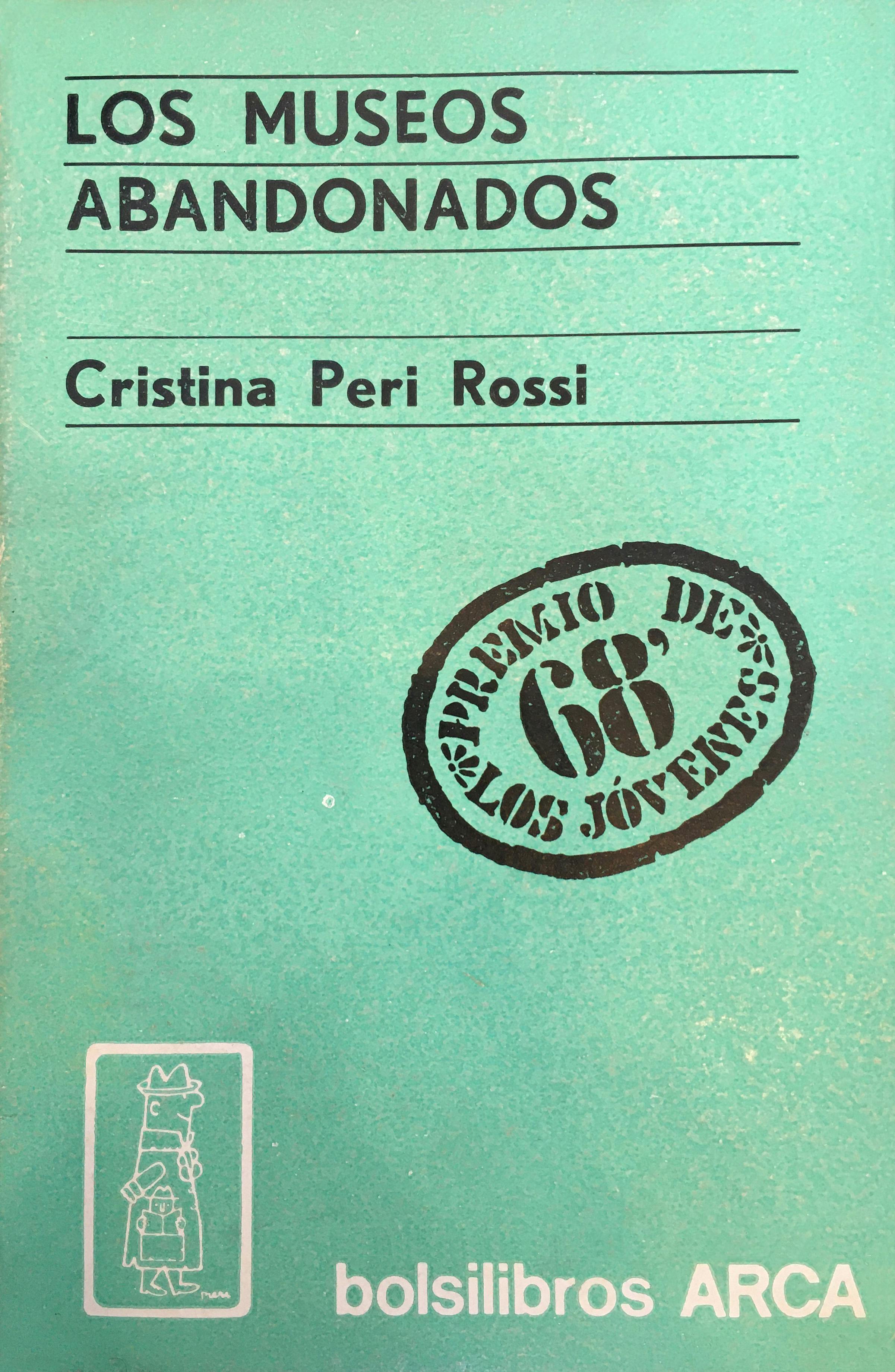

Fig. 1. Cover of Los museos abandonados by Cristina Peri Rossi (Montevideo: Editorial Arca, 1969). Illustration by Carlos Pieri

Fig. 2. Cover of La ciudad by Mario Levrero (Montevideo: Tierra Nueva, 1970). Illustration by Domingo Ferreira

Amid the unsettling social and political scene that had been brewing in Uruguay since 1968, artistic production took a drastic turn toward the medium of drawing. This technique offered a more direct form of expression at a time when artists desired to capture the moment, rebel against oppression, and critique it through the use of both humor and horror.

Uruguayan Literature

It is impossible to include in this short essay the immensity of Uruguayan authors that were writing and publishing novels between the mid 1960s and early 70s, coinciding with the production of drawings from El Dibujazo. Mario Levrero and Cristina Peri Rossi, born in 1940 and 1941 respectively, exhibit distinct narrative styles: oneiric Kafkaesque in the case of Levrero versus Peri Rossi’s baroque satire. Despite these differences, the pair has been named the “irrealistas” (irrealists) due to their shared ambivalent relationship with reality. 7

My points of entry into Uruguayan literature of the 1960s and 70s are Levrero’s first novel, La ciudad (The City) 8 , and Peri Rossi’s short story “Los extraños objetos voladores” (The Strange Flying Objects) from her second book, Los museos abandonados. 9 Reading these stories in tandem with Dibujazo drawings, it is evident that they share a despise of a hegemogenic reality. Certain subjects are present in both texts and images. Coincidentally, both texts were illustrated by Dibujazo draftsmen. This confluence, which initially seemed serendipitous, reflected the deep and close working relationship between Dibujazo artists and writers.

Peri Rossi’s Uruguayan edition of Los museos abandonados features cover art by Carlos Pieri (fig. 1). The artist had been commissioned by Arca Editorial, a publishing house funded in 1960 by prominent literary critic Ángel Rama, to design the series cover art for its paperback imprint Bolsilibros. His drawing shows a man in profile standing under a streetlamp wearing a hat, and in his coat pocket, a miniature man reading a book. The cover of Levrero’s La ciudad was designed by Domingo Ferreira and displays a black line-drawing of a man, in a shirt and tie, looking pensive against a white background (fig. 2). The folds of his shirt are so voluminous that it is impossible to distinguish arms from body, front from back—a reference to the spatial and temporal distortions that take place in the story.

Both La ciudad and “Los extraños objetos voladores” create immersive atmospheres filled with strangeness and absurdity. In Peri Rossi’s short story, we meet an elderly couple, Lautaro and María, who live in a remote countryside area. In the opening scene, their lives are disrupted when they discover a brown object flying above them, seemingly observing them. María thinks of the object as company, and is concerned about its lack of rest, being out there all alone in the sky. Lautaro, in turn, soonafter develops an optical deficiency that causes elements to vanish from his field of vision. First, his face and body begin to disappear, then his bed, his tools, and the trees outside his house. During dinner one evening, he refuses to put his fork down on the table, fearing that once out of his hands, it too will vanish. As Lautaro begins to spiral into paranoia, no longer able to differentiate between reality and illusion, he makes a visit to a doctor in the neighbouring town. Without much hesitation, the doctor gives him a pill, and suggests that he look at himself in the mirror. Miraculously, the viejo has recovered his missing side. He heads back home content and relieved only to discover, once he arrives, that everything has vanished: his home, his wife, and the trees have disappeared, leaving only dry soil behind.

Levrero begins his novel with a quote from Kafka that describes a city on the horizon that does not materialize beyond its blurry outlines, an epigraph that foretells what will unravel in the story. We are introduced to an unnamed first-person narrator for whom we are provided no spatial reference other than that he is inside an old, damp, half-empty house. We do not learn why he is there, how long he intends to stay, or how he arrived at the house. As with the rest of the story, scenes unfold in a dreamlike fashion. After leaving the house in search of food, the main character not only fails to find a shop but descends into a nightmareish adventure where space and time collapse. He walks for hours down roads leading nowhere, eventually encountering a woman, Ana, who despises him yet seduces him. She later disappears with another man once they reach the town. When the narrator asks the people in “the city” for directions to her house, they are unable to provide them, despite knowing its location. The narrator eventually makes a friend, Giménez, who offers him a place to stay, but, continuing in the vein of the mysterious and nonsensical, he provides labyrinthical directions to his room, and lies about knowing the woman he’s trying to find. The events surrounding this character are difficult to comprehend yet easy to accept, reminiscent of the Kafkaesque sense of the inexplicable yet familiar.

Whereas Peri Rossi breaks the narrative pact of realism with the reader from the outset by introducing an intentional flying machine/creature, Levrero takes a more gradual approach, progressively dissolving the boundaries of reality as we follow the character through seemingly neverending adventures.

Fig. 3. Alberto Schunk, Carpeta negra, 1973. Ink and watercolor on paper, 20 1/16 × 15 9/16 in. (51 × 39.5 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

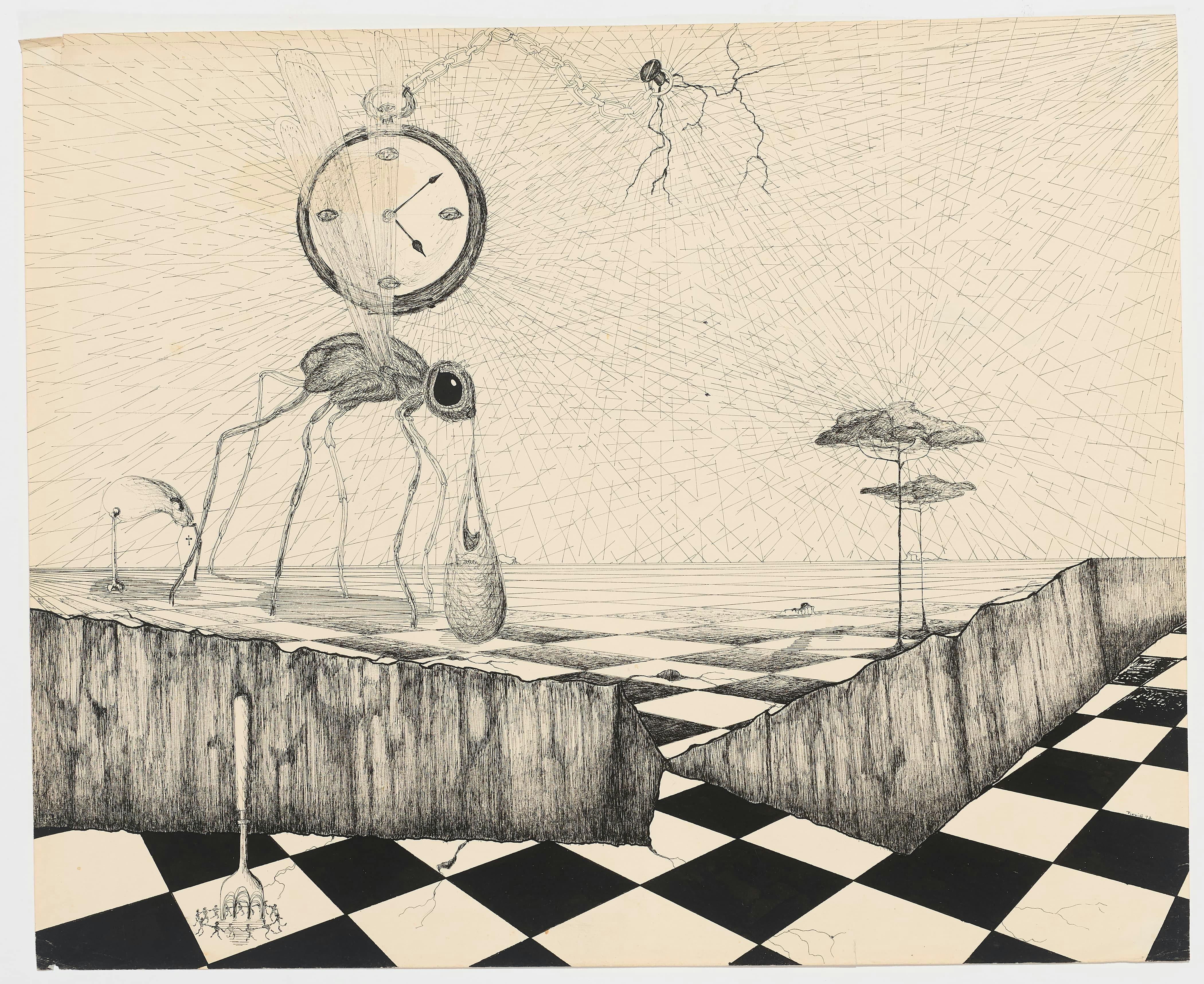

Fig. 4. Beatriz Battione, Untitled, 1972. Ink on paper, 23 5/8 × 19 5/16 in. (60 × 49 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

Reading Uruguayan literature of the 1960s and 70 (Mario Levrero’s novel La ciudad, and Cristina Peri Rossi’s short story “Los extraños objetos voladores”) in the company of the El Dibujazo drawings makes it evident that they shared a despise of a hegemogenic reality, and certain subjects where present in both texts and images.

A Distorted, Surveilled Atmosphere on the Brink

What kind of intensities do we encounter in these stories and how are they conveyed in the drawings that accompany them? In what ways do these texts facilitate our appreciation of and attunement to the artworks? This essay considers how these narratives activate and affect our perception of the accompanying Dibujazo artworks. In navigating this atmospheric shift, images selected from ISLAA’s archive—by Alberto Schunk, Beatriz Battione, Eugenio Darnet, and Eva Aldama—are presented not merely as illustrative or representative but as comprising independent works that echo the thematic concerns and sentiments expressed in the stories of Levrero and Peri Rossi.

Distortion

In these images and the mentioned stories, time and space are distorted. In Schunk’s drawing (fig. 3), walls, floors, and ceilings wrap, contour and dissolve, blending into one another—a literal unfolding of space. Similarly, in Levrero’s story, as the narrator walks endlessly, he notices that “the blocks were not even, but took on strange shapes, even circular and elliptical.” 10

In Beatriz Battione’s drawing, it is the scale that appears deeply warped (fig. 4). Her image transforms the domesticity of a checkerboard flooring into an infinite field interrupted by two hidden precipices. The sky, full of lines, appears shattered or on the verge of collapse, evoking the fragility of the moment. While there is no fog, some thin, intersecting lines are visible on the horizon. Central to the drawing is a gigantic creature—an animal made up of many others standing large and tall next to miniature trees, not far from an immense fork.

Surveillance

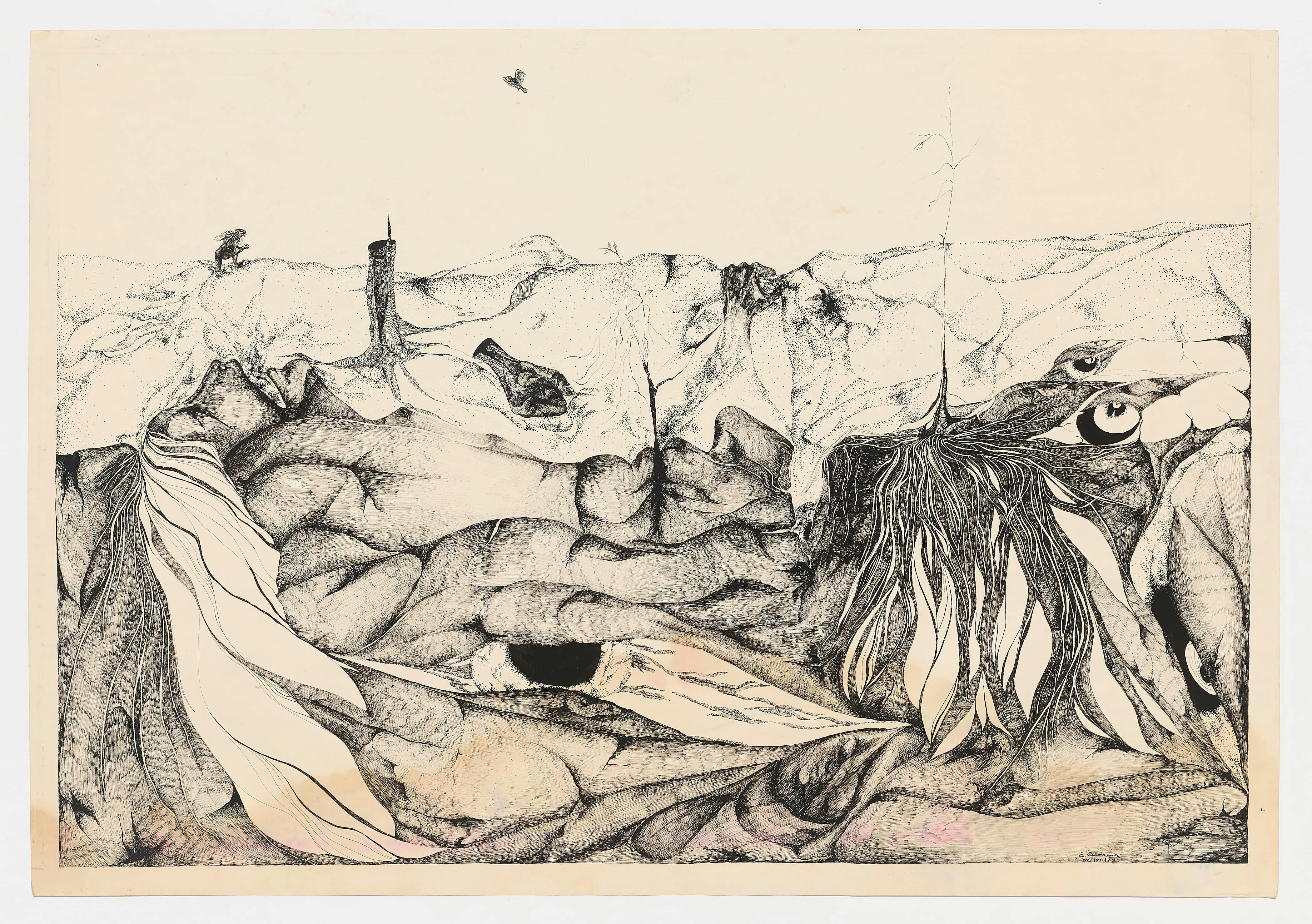

The unnamed narrator in Levrero’s novel does not experience surveillance per se but does, at times, expresses perplexity at how the generous Giménez seemingly anticipates his needs. With no solicitation from the narrator, Giménez prepares a table with food and washes and folds his clothes. In the drawings by El Dibujazo artists, surveillance is often symbolized by the presence of an eye. In his untitled drawing from 1972, Eugenio Darnet captures one of the most striking and terrifying gazes present in this collection (fig. 5), where an eye appears to merge with what resembles a foot with a single toe or a tongue. Battione saturates her image with eyes as well, depicting an ant-spider-fly creature with a disproportionately large black eye that occupies most of its face. Drowsy eyes also appear inside the watch that hangs from the collapsing sky. Aldama conceals large, half-open eyes in the amorphic ground of her drawings (fig. 6). In Peri Rossi’s story, the bird-animal-machine looms in the air over Lautaro and María’s home in the dry countryside, unabashedly watching over them:

“The brown object drifted unhurriedly through the air, between one cloud and another. It moved slowly, as if looking at them.” 11

In the drawings by El Dibujazo artists, surveillance is often symbolized by the presence of an eye. In his untitled drawing from 1972, Eugenio Darnet captures one of the most striking and terrifying gazes present in this collection, where an eye appears to merge with what resembles a foot with a single toe or a tongue.

Disappearance and Abyss

Disappearance is at the heart of the plot of Peri Rossi’s politically charged short story, which contains an explicit epigraph dedicated to the guerrilleros. This motif comes to the forefront when Lautaro makes a curious discovery:

"He could no longer see the trunk of a eucalyptus tree, and this really made him laugh, because the only thing he could no longer see was the trunk: the highest branches and the gray, hard, smelly leaves, he could see them well, as always: the tree only lacked the trunk and it looked funny like that, seeing a great void and above it the plume of branches and the leaves hanging down." 12

In Battione’s artwork, two abysses interrupt the otherwise continuous ground. Voids in the floor, connected by a thin edge, create a distinction between front and back, here and there. In Schunk’s fluid scene, characterized by a yellow background and convex forms, along with the transformation of bricks into bones, hint at the possibility that this landscape that we are seeing may be sinking and disappearing, mirroring the theme in Aldama’s drawing, where the collapse of background and foreground, the merging of below and above ground, leaves the human character on her knees, with tree trunks barely discernible on the horizon.

Certainly, El Dibujazo is more than an atmosphere. But the claim that it embodies one, characterized by certain qualities, conjures the collective spirit shared across the individual artworks. Distortion, disappearance, and surveillance are a few of the many readings one could make. No single quality is taken up by all artists, and likewise, no characteristic exists in isolation—they echo and resonate within one another.

During a review of the exhibition El Dibujazo that took place at the Centro de Exposiciones at the Palacio Municipal in Montevideo in 1990, more than twenty years after the creation of the artworks, Gabriel Peluffo Linari observed that certain drawings lost their dramatic, charged, and promising atmosphere when viewed in a different historical and political context. 13 My decision to incorporate literature is, in some way, an attempt to immerse these depictions in the sentiments of their time, without purporting to resurrect the historical horrors that surrounded their creation.