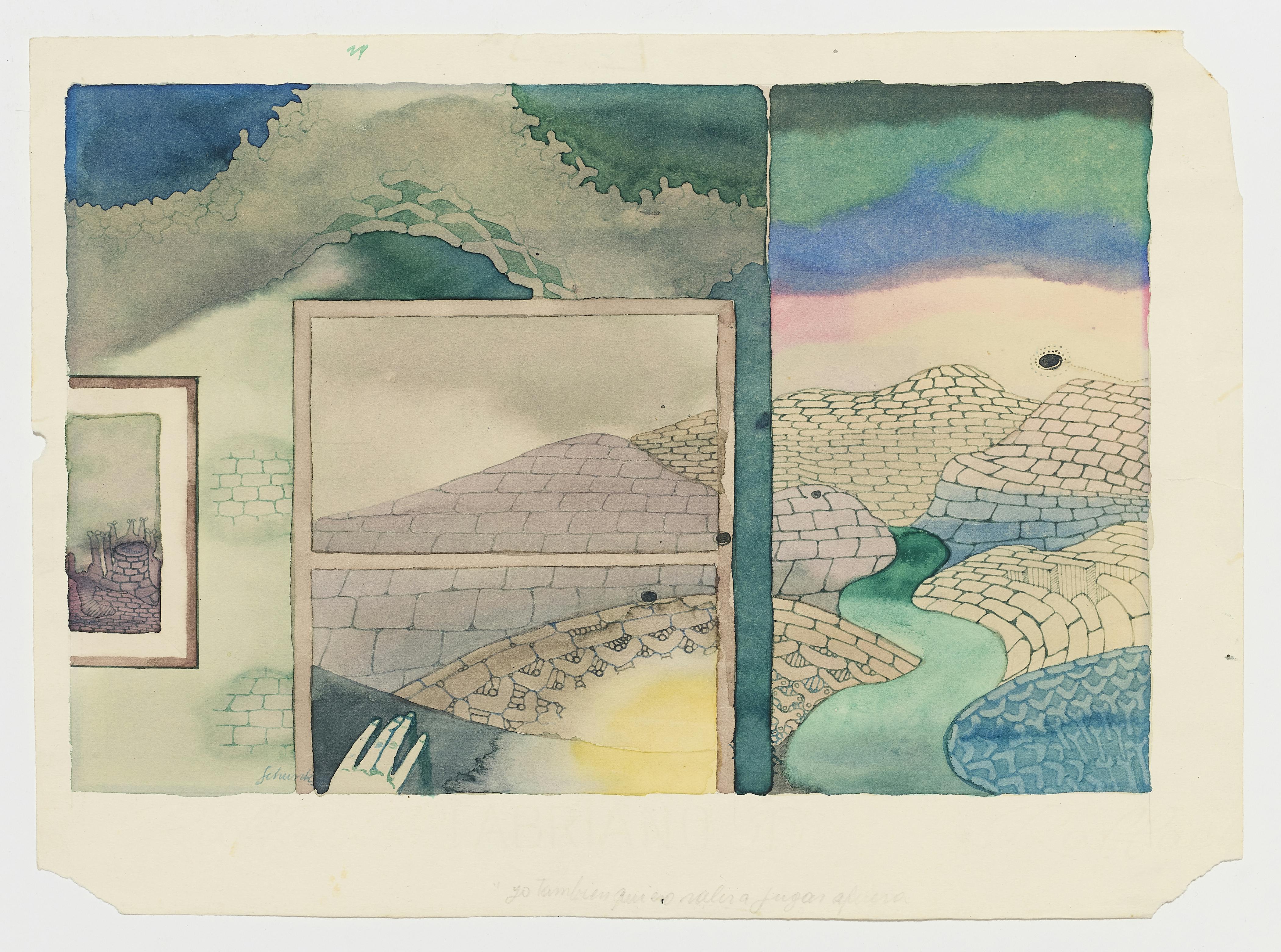

Alberto Schunk, Yo también quiero volver a jugar afuera, Carpeta negra (I Also Want to Play outside Again, Black Folder), 1972. Ink and wash on paper, 9 7/16 × 12 63/64 in. (24 × 33 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

The Writer in Residence series offers scholars the opportunity to conduct research on Latin American art through materials in the ISLAA Library and Archives.

During the latter part of the twentieth century, a notable shift toward drawing occurred throughout Latin America. This surge, often referred to as “the Boom,” can be attributed to several factors. The curator and author Edith Gibson has provided a detailed explanation of how international competitions, biennials, and local gallery exhibitions made space for drawings, thus allowing illustrators to gain popularity both locally and abroad. 1 The separation of drawing from the more general grouping of “graphic arts” at these events also enhanced the practice’s visibility. Drawing fulfilled different purposes than other works on paper, such as posters and prints. While the latter can be easily reproduced and distributed on a large scale, a single drawing done by hand has a much more limited audience. For this reason, drawings often have a more personal and experimental nature, which should not be confused with being apolitical.

The rise of far-right dictatorships in the Southern Cone of the Americas from the 1960s onward introduced a period of widespread censorship and persecution. Artists were forced to either find imaginative ways to communicate their ideas or to fall in line with the government’s strict messaging. Many expressed the importance of separating art from the propaganda mill serving political interests, while others purposefully separated their work from the official discourse. 2 Simultaneously, artists working in the Caribbean attempted to develop a sense of identity while grappling with the continued effects of colonial occupation and the Middle Passage. The result was a collective undertone of resistance throughout the Americas, where artists collaborated on an international scale to devise their own rules of artmaking rather than follow those imposed by colonial or military rule. These networks, which were dependent on correspondence and international travel, took advantage of the versatility and immediacy of working with paper.

In this essay, I focus on the artistic movement of El Dibujazo, a term coined in the early 1970s to describe a group of young Uruguayan artists who adopted drawing as their primary medium. 3 Developing against an increasingly violent backdrop and after decades of economic turmoil, the movement used imaginative lines and subject matter to comment on current events and social changes. The works included in this group vary greatly in style and theme, but they share a commitment to employing a new visual language to capture their audience’s attention. In the words of Néstor Canessa, the group’s intention was to “insert the possibilities of the artist into the masses.” 4 At a time when art production was restricted by military oversight, El Dibujazo attempted to place human emotion and creativity at the forefront of an otherwise suppressed cultural environment.

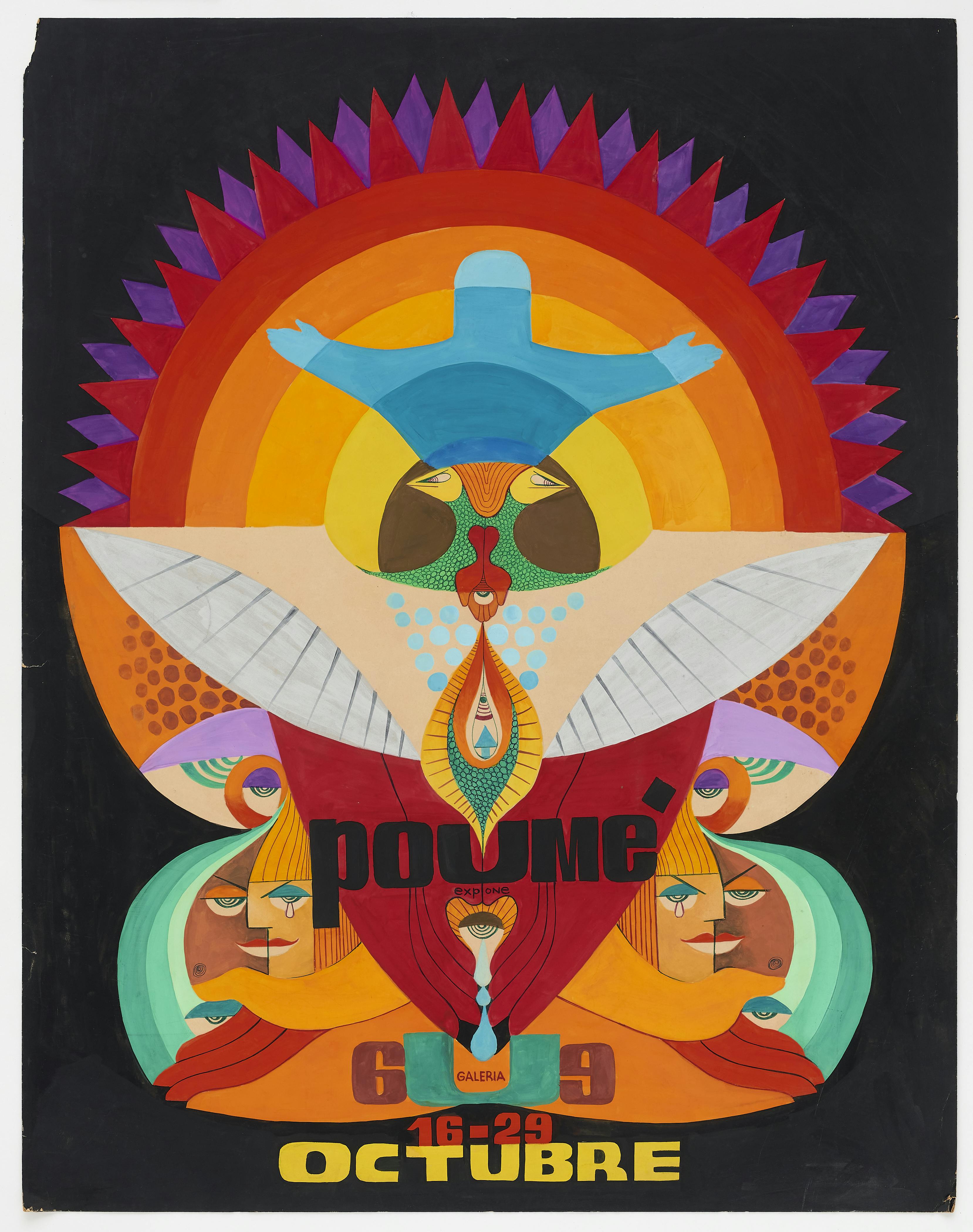

Fig. 1. Unknown artist, Poumé expone, Galería U (Poumé Exhibits, Galería U), 1969. Acrylic paint and ink on paper, 36 1/4 × 28 3/8 in. (92 × 72 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

Artists responded to this increasingly hostile environment of the military dictatorship in various ways, incorporating humor, satire, and an overarching reassessment of established norms.

Often referred to as “the Switzerland of South America,” the small country of Uruguay had long been mythicized as a liberal and democratic counterpart to its neighboring countries. However, in the 1950s, symptoms of an economic crisis started to erode the nation’s seemingly utopian foundation, and the effects were exacerbated by the implementation of a collegiate presidency under President José Batlle y Ordoñez in 1952. 5 This change meant that the executive branch would be led by multiple people simultaneously—a measure designed to prevent the rise of a dictatorship by forcing collaborative decision making. Unfortunately, the collegiate approach led to the destabilization of the Uruguayan government due to a lack of clear leadership, internal disagreements, and the ongoing financial difficulties of the time. 6

The economic crisis continued for several years, and circumstances worsened with the rise of a revolutionary left known as the Tupamaros, named after the 1780 Tupac Amaru Rebellion in Peru. 7 Their initial “Robin Hood-esque” activities included robbing local banks and businesses and subsequently redistributing the stolen goods among poor communities in Montevideo. Their actions later escalated to kidnappings and political assassinations, which prompted a severe response by the Uruguayan military. In 1973, President Juan María Bordaberry suspended the constitution and banned all political activity in an attempt to restore order. The result was a military coup and a decade-long dictatorship characterized by mass arrests, torture, the disappearance of political prisoners, and censorship, lasting until 1985. 8

Artists responded to this increasingly hostile environment in various ways, incorporating humor, satire, and an overarching reassessment of established norms. During the 1960s, a generation of young illustrators and printmakers gained prominence in the Montevideo art scene. 9 Spaces such as Galería U and the Centro Uruguayo de Promoción Cultural (later known as Galería Alfa), under the leadership of the art dealer Enrique Gómez, organized solo shows around drawings and prints. Many well-established institutions, including the Instituto de Artes Visuales Poumé, also staged events and galleries dedicated to drawing (fig. 1). Illustrators went on to participate in international biennials in neighboring countries, such as Brazil and Argentina, while establishing relationships with artists in the United States, the Caribbean, and Europe. 10

During these difficult times, correspondence and international collaboration became a lifeline for artists living in Uruguay and abroad. Limited by government interference, artists working in Uruguay looked to exhibit their work elsewhere.

During these difficult times, correspondence and international collaboration became a lifeline for artists living in Uruguay and abroad. As elaborated in a letter between the artist Quela Rovira and the Puerto Rican printmaker Lorenzo Homar, the effects of censorship rapidly spilled into the cultural sector, where they affected exhibition spaces and sales. 11 In the letter, Rovira explains,

The situation here is very difficult and sad; Uruguayans emigrate in search of jobs and for political reasons . . . The ones who stay are those well accommodated by the government or those, like us, who are of a mature age . . . I believe it will only get worse given that they have presented a new law that states that government employees (teachers, professors, medics and public health workers, etc.) who are thought to have belonged to any of the outlawed groups will be forced to leave their posts.

La situación aquí, es muy difícil y triste; los uruguayos emigran por falta de trabajo y también por razones políticas. … Aquí se quedan los que están acomodados por el Gobierno y los que, como nosotros, por estar ya en la madurez y tener el trabajo en Uruguay, se nos hace muy difícil comenzar a punto 0 en otro. Creo que muy próximamente se agudizará más esto pues han proyectado una ley por la cual todos los empleados del Gobierno (empl. Públicos, maestros, prof, médicos y empl. de Salud Pública etc.) que hayan pertenecido a cualquiera de las agrupaciones declaradas fuera de la ley, serán declarados ineptos para seguir en su puesto. Rovira to Homar, September 27, 1974.

Fig. 2. Clipping of the article “Generación de dibujantes (II),” Gabriel Peluffo, published in the Uruguayan newspaper Marcha, July 28, 1972. Courtesy Gabriel Peluffo. Anáforas, Publicaciones Periodísticas del Uruguay

In this letter, what starts as a discussion of logistics and art sales quickly evolves into a briefing on the current circumstances in Uruguay. It showcases the urgency of the situation at hand and the importance of relationships between artists from different backgrounds who were connected by a commitment to defending their right to creative liberty.

Limited by government interference, artists working in Uruguay looked to exhibit their work elsewhere. In a letter to Leonilda González, a Uruguayan artist and the Secretary General of the Club de Grabado de Montevideo (Printmaking Club of Montevideo), the Puerto Rican multimedia artist Antonio Martorell assesses possible venues for a collective show featuring works from both Uruguay and Puerto Rico. 12 Martorell notes the political affiliations of each venue’s organizers, stating that the left-leaning sector would be more welcoming of such a production and could offer a “kind of escape valve . . . a refuge for nationalists.” 13 Martorell exhibits an awareness of the political landscape plaguing Montevideo as well as his native island, given that cultural production was under scrutiny in both contexts.

Both Rovira’s and Martorell’s letters attest to the importance of international art networks during the 1960s and 1970s for both commercial purposes and personal support. In Rovira’s case, we can see firsthand how political censorship suppressed cultural and social activities, in turn creating migration waves that would alter the artistic landscape for decades to come. Martorell’s letter, which was written one year later, exemplifies how artists at the time were actively seeking outside channels to exhibit their work instead of conforming to strict national norms. Repressive systems thrive by forcing their victims into isolation, while personal relationships, such as those cultivated by artists working in Latin America, serve as a resistance strategy. In the words of Martorell, “To you our most gracious memories and hopes for a better world, which we will create together, and those who will come after us.” 14

Local networks within the Montevideo art scene were of equal importance to those on an international scale. In addition to working with the galleries mentioned above, artists also served as illustrators for local publications, many of which were very outspoken about their opposition to the rising regime. One such publication was Marcha, a weekly editorial that allowed artists to experiment and create recurring characters (fig. 2). In fact, it was in an issue of Marcha from 1972 that the term “Dibujazo” was first coined by the author María Luisa Torrens. 15 The editorial writers’ open denunciation of the dictatorship and its abusive practices caused the publication to be swiftly shut down less than a year after the military takeover of 1973. 16 Many artists who are considered part of El Dibujazo contributed to the publication during its active years.

Fig. 3. Marta Restuccia, Los pobres amantes II (The Poor Lovers II), 1972. Ink and wash on paper, 23 1/4 × 19 1/8 in. (59 × 48.5 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

Despite all their variations, a common thread throughout the works under the El Dibujazo umbrella is their exploration of the more somber sides of human emotion, which directly relates to the harsh context in which these artists lived.

Certain recurring themes have been identified as characteristic of the drawing movement in Uruguay. The diverse subject matter ranges from the fantastical and romantic to the gruesome and bizarre (fig. 3). Likewise, a variety of materials were used in works of the time. While ink and charcoal were the base for most sketches, many artists incorporated watercolor or wash to accentuate different tones and add dimension to their drawings (fig. 4.) In addition, the rapidograph was a very popular tool for producing consistent, efficient lines to meet the quick turnaround time demanded by the rapidly evolving news cycle. 17 Despite all these variations, a common thread throughout the works under the El Dibujazo umbrella is their exploration of the more somber sides of human emotion, which directly relates to the harsh context during which they were created.

Eduardo Fornasari, who is considered one of the fathers of the drawing movement in Montevideo, experimented with crosshatching and shading to create a sense of multidimensional space while exploring layers of consciousness. In an untitled work by Fornasari from 1965, an older figure stands in the foreground in front of a shattered window (fig. 5). A half-formed silhouette appears in the glass, and its borders vanish into the shadows of the windowpane. The edges of the man’s carefully rendered mustache and cheek are lifted toward the empty space between the man and the back wall, transforming into a formless blob of scratched lines and dimpled crevices. In an interview with Marcha in 1972, Fornasari explained how his early works attempt to unveil the psychology of man “through an emaciated portrait of what lies behind the masks.” 18 In a literal sense, we can see how Fornasari removed the boundaries of the figure’s face, thus allowing his once-hidden, deformed psyche to spill outward into plain view.

In the same interview, Fornasari stated that he no longer wished to unmask the deep corners of the human mind and instead wanted to show people from the outside “as I see them.” 19 However, in the early 1990s, he seemingly returned to his initial focus in a work depicting an actual mask covering a web of deformed faces with popped eyes and dripping noses (fig. 6). Although a democratic system had been reinstated by this time, the residual effects of the decade-long dictatorship remained palpable across Uruguay, and the military regime had yet to be indicted for their crimes. 20

Fig. 7. Heber Freddy Marchisio, Untitled, 1972. Ink on paper, 19 11/16 × 25 ½ in. (50 × 64.7 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

Fig. 8. Heber Freddy Marchisio, Untitled, 1971. Ink on paper, 12 63/64 × 11 13/16 in. (33 × 30 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

Many illustrators explored the human psyche, while others exposed their own tortured psyches as creatives.

Many other illustrators echoed Fornasari’s exploration of the human psyche, including Heber Freddy Marchisio (fig. 7). In a potent statement, Marchisio said plainly, “I cannot sit and draw something beautiful. I do not see anything beautiful around us.” 21 His works feature deformed figures whose skin is peeled back to reveal a conglomeration of naturalistic elements connected by cables and columns, pockets of stones, and buttons nestled into machinelike forms. Marchisio’s characters are those of tortured men, whom he considered representative of the “contemporary Uruguayan man.” 22 It is no coincidence that El Dibujazo is often described in terms of monstruitos, or “little monsters,” in reference to the often-distorted figures at the center of many of these works (fig. 8). 23 These little monsters represent the tortured minds of people who lived in the midst of constant violence and were forced to grapple with monstrosities in their daily lives.

In other instances, artists exposed their own tortured psyches as creatives. For example, in Tranquilízate mente (Calm Down, Mind), Gabriel Constantino presents an elaborate composition of all of the folds of human consciousness plagued by the nonstop influx of outside information (fig. 9). Deformed faces and ears seem to take the shape of artists’ palettes surrounded by floating squares that are not unlike blank sheets of paper. A main figure stares blankly out at the beholder, frozen and distorted by the storm of objects emanating from every corner of the composition. Beneath it all, fragments of a checkered board transform the scene into a chess game gone wrong, as the artist struggles to strategize and organize his ideas under the weight of an anxiety-inducing reality.

While these works constitute acts of resistance, they also provided an emotional release. The works of Alberto Schunk in his Carpeta negra do not depict monsters or distorted faces but rather empty rooms filled with nostalgic recollections of the past (fig. 10). Composed of both drawings and prints, in this illustrated series, the artist longs for the liberty to roam and, by extension, to create, as suggested by titles such as Yo también quiero volver a jugar afuera (I Also Want to Play outside Again) (fig. 11).

El Dibujazo is the name for a group of young artists who struggled to find their voices amid an ongoing attack on social and cultural institutions, freedom of speech, and the right to live freely and peacefully in Uruguay during the rise of a military regime. In their works, the distortion of human figures on paper echoes the distortion of these artists’ realities. As they were unable to explicitly denounce the monster towering over their once peaceful country, these illustrators used drawing to create a fantasy realm in which they could face monsters made by their own hand. On paper, these monsters could be defeated. This collection of works is just a small sample of those hard-won battles—offering a possible blueprint for work that must be continued.