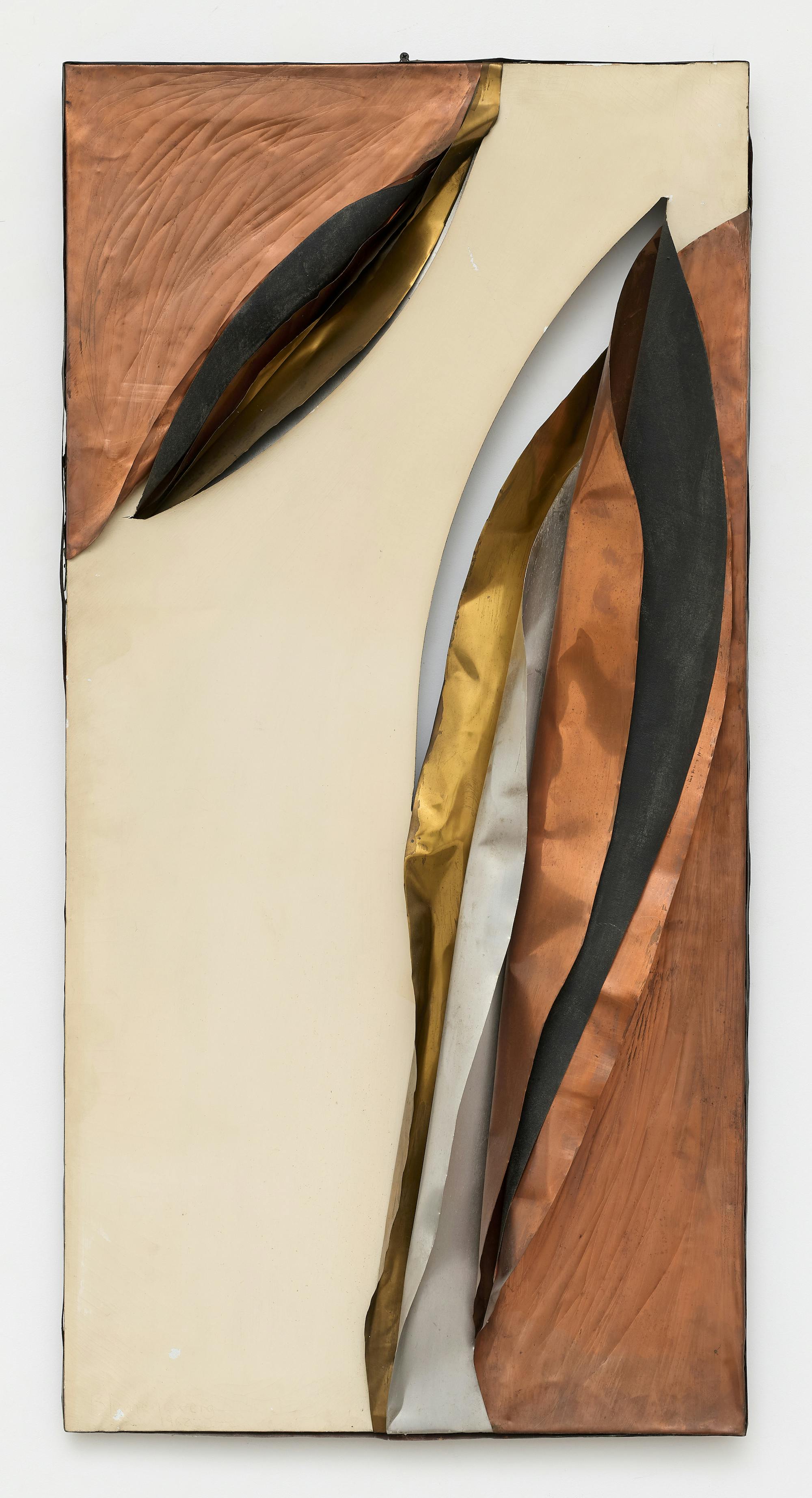

Fig. 1. Inés Blumencweig, Double face (Double Sided), 1962. Acrylic paint and metal on canvas in wooden artist’s frame, 36 1/4 × 32 1/8 × 1 1/2 in. (92.1 × 81.6 × 3.8 cm). © and courtesy the artist. Photo by Arturo Sánchez

Re: Collection invites a range of historians, curators, and artists to respond to the artworks in our collection through approachable texts.

After moving to Rome in the early 1960s, the Argentine artist Inés Blumencweig (b. 1930) abandoned her Surrealism-inflected paintings for starkly minimal canvases punctuated with slashes and extrusions of metal. Working with the cheap industrial material of postwar Italy, Blumencweig’s frequently wall-based practice evolved as a series of complex articulations of space—neither painting nor sculpture and without the illusions of depth deployed by her contemporary, Lucio Fontana. Diving into an exploration of the artist’s spatial strategies through comparison to Fontana’s Tagli, curator and writer Amanda Schmitt identifies Blumencweig’s radical experimentation with the picture plane as an important intermediary between Italian Arte Povera and Brazilian Neo-Concretism.

Fig. 1. Inés Blumencweig, Double face (Double Sided), 1962. Acrylic paint and metal on canvas in wooden artist’s frame, 36 1/4 × 32 1/8 × 1 1/2 in. (92.1 × 81.6 × 3.8 cm). © and courtesy the artist. Photo by Arturo Sánchez

Fig. 2. Inés Blumencweig, Double face (Double Sided), 1962. Acrylic paint and metal on canvas in wooden artist’s frame, 36 1/4 × 32 1/8 × 1 1/2 in. (92.1 × 81.6 × 3.8 cm). © and courtesy the artist. Photo by Arturo Sánchez

Born in Buenos Aires between the World Wars, Inés Blumencweig developed as a Surrealist-leaning young artist, debuting her work at various salons and galleries in Argentina through the 1950s. She married a painter of note (the Informalist Mario Pucciarelli) and the young couple set off to North America, spending time in Washington, DC and New York before arriving in Rome in the early 1960s, where they eventually settled. Perhaps inspired by the prevalence of Abstract Expressionism, which she witnessed while meeting other artists in New York, it was during this decade that she departed from representation and produced radically innovative abstract artwork. Blumencweig’s primary contribution to the development of abstract art in the postwar period was the disruption of continuity in the picture plane: she sought to challenge the separation between painting and sculpture, expanding painting into the third dimension.

This pursuit to dissolve the boundaries between painting and sculpture was shared by another Argentine immigrant, the influential Lucio Fontana. The similarities between the work of these two artists are not coincidental, as they orbited the same social and intellectual circles, exhibited alongside each other, and had their work discussed—at times in relation to each other—in various catalogues and by the Italian press. In Fontana’s seminal Concetto spaziale series, his Tagli (cuts) and Bucchi (holes) blast open the surface of a canvas to reveal the void behind it, simultaneously destroying the illusion of a picture and thrusting the material aspects of the art object into the space it shares with the viewer. However, Fontana’s paintings always maintain a plane, with a verso and a recto, and it is the front side that was always meant to be presented. We could say that the illusion recedes “behind” the ruptured plane but does not disappear entirely. In fact, Fontana deliberately affixed black cloth to the back of his Tagli to deepen the semblance of a void.

Certainly, Blumencweig (and many others) drew great inspiration from Fontana’s radical gesture of piercing the picture plane, yet she also interpreted his manifestos 1 and expanded on his ideas. Consider Double face (Double Sided, 1962) (figs. 1 and 2), a remarkably complex and dynamic composition that presents itself as a quadrilateral white painting. A wide horizontal cut is made across the latitudinal center of the canvas, revealing not an illusionary and constructed void (as with Fontana’s Tagli) but the wooden stretcher bar itself. A convolution of roughly a dozen irregular vertical incisions is rendered on the upper half of the canvas, which twists and curls around itself. A bronzed metal ribbon weaves through the center horizontal stretcher bar and encircles the lower half of the canvas as a decisive vertical stripe, further indicating that the artwork itself is not simply two-sided but absolute in form. Its composition is not perceptually apprehensible solely through a frontal view. Blumencweig transforms the picture into a sculpture, obliterating painting’s traditional verso-recto dialectic.

In 1971 the renowned Italian art historian Enrico Crispolti 2 made a clear distinction between the Spatialist project of Lucio Fontana and Blumencweig’s innovations:

Fontana fractured the spatial absoluteness of the canvas’s surface. Blumencweig, on the other hand, appears to have in some way reversed the terms of the question: she doesn’t display an exteriority of space, infinite, limiting the finite surface. Instead, in a manner that transcends the surface as such, she demonstrates a penetration of space and into space through the structure itself. Fontana imaginatively alludes to an undoubtedly cosmic opening to an infinite space, while Blumencweig, by contrast, seeks to enclose the presence of a mystery within the dimension of space. 3

Fig. 3. Inés Blumencweig, Irrupción en el plano (Irruption into the Plane), 1962. Acrylic paint on canvas and metal, 47 1/4 × 23 1/2 × 3 1/2 in. (120 × 59.7 × 8.9 cm). © and courtesy the artist. Photo by Arturo Sánchez

Blumencweig transforms the picture into a sculpture, obliterating painting’s traditional verso-recto dialectic.

The “penetration of space and into space” through the utilization of surfaces represents a shift toward an investigation of the topological: 4 Blumencweig considers the unified nature of the object, creating unity from plurality by melding and marrying the canvas, the paint, and the stretcher bars together. In works such as Double face, Blumencweig stretches, twists, and distorts the constitutive objects (the canvas and metal sheets) while keeping them materially recognizable and differentiated. The work could be construed as her hypothesis, proof, and thesis.

Her experiments in topology thus establish a close connection with the Neo-Concretist movement that was concurrently developing in 1960s Brazil. While Blumencweig made no known trips to Brazil, and it was unlikely she was in direct dialogue with Neo-Concretist artists, Blumencweig’s object-paintings are both affectively and formally comparable to Lygia Clark’s Bichos (Critters) (fig. 4) 5 and even Hélio Oiticica’s Relevo espacial (Spatial Relief) 6 in emphasizing the bodily experience of a work of art.

There is, additionally, a material resonance that aligns with the rapid postwar industrialization of both Brazil and Italy. Just as Blumencweig’s use of readily available metals reflects and comments on the economic growth of Italy in this period (as Clark’s work comments on that of Brazil) and the subsequent availability of new consumer materials, artists of other disciplines also envisioned the urban degradation that was intertwined with postwar prosperity, as depicted in Michelangelo Antonioni’s iconic cinematic industrial landscapes (in films like L’Eclisse, 1962, or Red Desert, 1964).

In Untitled (1961) (figs. 5 and 6), a band of what appears to be bronzed aluminum encircles and weaves around the rectilinear wood stretcher bars and through the white-primed canvas, dissected by two vertical slashes and a half-moon shaped hole, through which the metal band is threaded. The metal has been vigorously scratched with a blunt, fine-pointed tool, to the extent that it has become embossed in relief. Some of these repetitive scores are horizontal, others are vertical, and some cross each other. While the hand that made these marks must have exerted a significant amount of pressure, the marks themselves appear somehow ethereal, as if emerging through a breath. This perceived dissonance between force of action and delicacy of the mark is a phenomenon produced by the luminosity of the metal surface.

In another work from the same year (figs. 7 and 8), a scrunched, crumpled, and flattened metal band sandwiches a strip of canvas, dividing two voids into semi-ovoid shapes. In contrast to Clark’s Bichos, which are modeled from a perfect geometry and welded neatly with joints, Blumencweig’s metal is gnarled, folded by hand, crumpled up against itself, deformed, and scratched. Her contortions of elastic metals bring to mind the traces of Fontana’s fingers in his ceramic work, marked by furrows and holes tracing the rough passage of these appendages through clay. Rather than evoking the groundedness of the earth, however, Blumencweig manages to make the metal feel light, as if it were being pulled up in the way that fire rises, licking the air. Nowhere is this elemental allusion clearer than in her untitled cadmium red work from 1962 (fig. 9). This composition goes beyond Fontana’s violent and decisive slashes: after the cuts have been made, the canvas is twisted and tangled to produce a dynamic and continuous curve where her incisions have been executed. Her tagli do not denote a disruption of a picture or a void. Rather, the negative space created by the lacerations to the canvas is instantly filled: the void becomes a volume. These spaces, in relation to the red canvas, transform into sensuous, even flamboyant forms.

From 1963 onwards, the canvas gave way to painterly arrangements composed predominantly of metal sheets rather than paint. In some instances, the works completed their evolutionary leap beyond painting into fully formed sculptures. This transition is what Crispolti aptly described as a “metamorphic matrix,” a concept embodied in compositions like Metales (Metals, 1963) (figs. 10 and 11) and Untitled (1964) (figs. 12 and 13). These paintings-cum-sculptures evoke an explosion, as if a bomb has blasted through a tin roof, yet the compositions also appear deliberate, ornamental even, like wrapped gifts carefully opened. They are at once annihilated and revelatory, conjuring both destruction and creation. In that sense, they stand in complementary contrast with Alberto Burri’s critical aestheticization of the new industrial reality of Italy in his Combustione series of burned plastics.

Nowhere is the metamorphosis more pronounced than in Struttura sensibile-nero-alluminio bianco (Sensible Structure-Black-Aluminum-White, 1964) (figs. 14, 15, and 16), a standalone structure that is roughly the size of a doorway, albeit one that can only be orbited and not penetrated. The frame is constructed of four slats of wood hinged together, painted white on the exterior and black on the interior, creating a tunnel-like effect. Wide ribbons of both raw and black-painted aluminum dance around the inner portion of the frame, rhythmically weaving into and out from each other in a graceful, fluid choreography, only to be nailed flat to the outer frame. This 1964 masterwork bears a clear (if unintentional) connection to the concurrent Neo-Concretism and Kineticism movements of that time, as the sculpture beckons the viewer to repeatedly approach and then step back—the approach to appreciate the fine detail and interweaving elements and the step away to regain a holistic perspective—encouraging a sort of pas-de-deux between viewer and object.

Fig. 17. From left to right: Inés Blumencweig, Natalio Povarché, Luis Felipe Yuyo Noé, Mario Pucciarelli, Rogelio Polesello, and unidentified, Buenos Aires, 1960. Courtesy Inés Blumencweig. Photographer unknown

The twentieth-century art scene in Europe, Latin America, and the United States was marked by male homosociality, with many great women artists privileging their husbands’ careers over their own. 7 Despite the prevailing patriarchal inequality of the period, by the mid-1960s, Blumencweig was exhibiting widely not only in Italy but also internationally, with exhibitions at the Museo de Arte Moderno de México, Museo de Arte Moderna de Rio de Janeiro, and the Modern Art Museum in Miami. At that time, her work was regularly discussed in journals of art criticism and reviewed by the press. Furthermore, for decades Blumencweig held a position as art critic for Italy’s leading news agency, Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata, and contributed to contemporaneous discussions of abstraction, among other movements in Italy and throughout Europe. Yet somehow, despite the innovation and dynamism of her practice and work, her name and legacy remain hidden in plain sight.

Like other women nonagenarian artists whose decades’ worth of remarkable work are only coming to light in recent decades (among them Carmen Herrera, Luchita Hurtado, Etel Adnan, and Vera Molnár), there’s a debt to history and a duty to reexamine, rewrite, and recirculate. I hope and anticipate that this cursory establishment of facts, places, and ideas will serve an origin point for further scholarship and research on Blumencweig’s extensive and protean body of work.