The first article ever published in Cal’s visual arts section (from the journal’s first issue, 1979): “La escena americana” (The American Scene), by Achille Bonito Oliva. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

The Writer in Residence series offers scholars the opportunity to conduct research on Latin American art through materials in the ISLAA Library and Archives.

The first issue of the Chilean journal Cal, arte expresiones culturales 1 was published in June of 1979, under the direction of Luz Pereira Correa. The journal brought together a considerable number of contributors, and its aim, as stated in the inaugural editorial note, was to report on “facts that ‘are' culture.” 2 This was not a minor undertaking; the journal upheld an understanding of culture that encompassed literature, poetry, the plastic arts, photography, music, and film, which it regarded as “the most profound sources of interest in current times.” 3 From the start, and throughout the journal’s run (a total of four issues were published), Cal featured articles, brief notes, interviews, and an event calendar of sorts, in an effort to cover all fields of cultural production. 4

The debates captured in Cal’s pages also shed light on the various discourses of Latin American Conceptualism as it developed between the 1960s and the 1980s, framed in the case of Chile by the consolidation of specific avant-garde artistic practices after the military coup of 1973.

Cal assembled a wide range of voices from all fields of cultural production, generating manifold and complex debates. A full analysis of these debates is beyond the scope of this text. 5 Instead, I will focus my attention on the debates that were taking place in the field of the plastic arts at the time, as recorded in the publication. By examining these debates it is possible to draft an overview of the confrontations that shaped Chile’s art scene during a period in which the country was under a dictatorship and art institutions struggled to respond to the country’s historical circumstances. The debates captured in Cal’s pages also shed light on the various discourses of Latin American Conceptualism as it developed between the 1960s and the 1980s, 6 framed in the case of Chile by the consolidation of specific avant-garde artistic practices after the military coup of 1973.

Cover of the first issue of Cal, 1979. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

The first article ever published in Cal’s visual arts section (from the journal’s first issue, 1979): “La escena americana” (The American Scene), by Achille Bonito Oliva. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Since its first issue, Cal functioned as a platform for the dissemination of cutting-edge artistic practices, their attending theoretical discourses, and the avant-garde traditions with which they engaged.

Since its first issue, Cal functioned as a platform for the dissemination of cutting-edge artistic practices, their attending theoretical discourses, and the avant-garde traditions with which they engaged. This is manifest in many of the articles published in the section devoted to the plastic arts, featured in all four issues. In the first issue, the section opened with an article titled “La escena americana” (The American Scene), a translation of a text by the Italian art critic Achille Bonito Oliva that diagnosed the avant-garde scene in the United States by drawing links to a European tradition anchored to the figure of Joseph Beuys, whose core endeavor was, according to the critic, “to promote awareness in the audience, to expand creativity toward social communication.” 7

Bonito outlines a genealogy for this tradition in the North American scene, including artists like John Cage, Allan Kaprow, Robert Whitman, George Maciunas, Nam June Paik, George Brecht, Henry Flynt, Robert Watts, and Dick Higgins, with various connections to European colleagues from the Fluxus sphere such as Wolf Vostell, Giuseppe Chiari, Tomas Schmit, or Robert Filliou. He calls attention to the emergence of new alternative spaces, self-run journals, and the discovery of Marxism, and concludes by claiming that American pragmatism seems to have lost its hold on the scene, giving way to collective forms of production exemplified by the Black Emergency Cultural Collection, the Creative Women’s Collective, the Guerrilla Art Action Group, Women in Arts, and Artists and Writers Protest, among others.

Juan Dávila’s article “El desnudo en el arte contemporáneo” (The Nude in Contemporary Art), published in the fourth issue, likewise examines affinities between avant-garde traditions. Through a collection of quotations about artists like Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Hans Bellmer, Konrad Klapheck, Man Ray, Andy Warhol, Richard Lindner, Valerio Adami, Chuck Close, and Carlos Leppe (among others), Dávila explains their approach to the nude and examines “male nudes in everyday environments, pornography, spectacle, and mass media, which he used as sources in his own work. He backs up his analyses with theoretical references from Susan Sontag, Severo Sarduy, and Jean-François Lyotard.” 8

Juan Dávila’s article “El desnudo en el arte contemporáneo” (The Nude in Contemporary Art), in issue 4 of Cal, 1979. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

These two texts are representative of Cal’s editorial position, aligned with European and US experimental practices and, most importantly, with local avant-garde practices. Support for the latter was not restricted to editorial policy, since the journal had links to a gallery space. The gallery, named CAL (short for Coordinación Artística Latinoamericana, or Latin American Art Coordination), was active throughout the 1970s in downtown Santiago, and it has been described as “the first gallery to work with young artists who had an experimental approach to art, and which also created a space for aesthetic reflection.” 9

"In the second half of 1979 and the first months of 1980 CAL welcomed the avant-garde works of Carlos Altamirano, Juan Dávila, Eugenio Dittborn, Alfredo Jaar, and Carlos Leppe, remembered as landmarks of Chilean art and a luminous conclusion to the gallery’s run. CAL’s final exhibition was Altamirano/Dittborn/Leppe/ visualizan: Purgatorio de R. Zurita, from January 8 to January 22, 1980, where the artists developed works based on the recently published book Purgatory by the poet Raúl Zurita." 10

A page from issue 3 of Cal, 1979, displaying ads for an exhibition at CAL in which Carlos Leppe would perform Acción de la estrella (Star Action), in which the artist established a direct dialogue with Marcel Duchamp, who was reinterpreted by Leppe. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Cal was an extension of a broader project directed at articulating and providing support to a set of avant-garde practices later described by the art critic and cultural theorist Nelly Richard as “la escena de avanzada” (the advanced scene).

In that sense, Cal was an extension of a broader project directed at articulating and providing support to a set of avant-garde practices later described by the art critic and cultural theorist Nelly Richard as “la escena de avanzada” (the advanced scene). 11 This designation encompasses the group of Chilean artistic and poetic-literary practices that stood out, starting in 1977, for experimenting with formats, languages, and techniques, and which operated at the margins of the regime. These experimentations decidedly challenged the academicism of Chile’s traditional art milieu, the official discourse of the dictatorship, and in certain cases the ideological sensibility of the orthodox left.

These practices are part of the strategies for thought developed by Latin American Conceptualism which, as Mari Carmen Ramírez has argued, always remained "in a dialogical situation with various artistic traditions from Europe and the United States. However, just like any other tendency originated in a non-hegemonic zone, the work [of Latin American artists] became tangled up in a model of assimilation/conversion broadly determined by the internal dynamics and contradictions of the local context. . . . The irruption of Conceptualism in Latin America follows these very closely, but in many crucial cases it also anticipated important developments in the hegemonic Conceptual art produced in central locations". 12

Cal offered a space for this discussion to play out, and the full scope of the questions at hand is registered in the first issue’s second article, titled “Dos enfoques de la plástica” (Two Approaches to the Plastic Arts), where Richard and the art critic Waldemar Sommer argued divergent takes. The positions that they outline offer us a glimpse of the state of the debate regarding Chilean art at the time. Richard, who was a regular contributor to Cal, represents those who argued that the emerging trends of artistic practice in Chile signaled the arrival of a higher degree of historical consciousness among artists, which entailed new production mechanisms; Sommer, for his part, failed to grasp them as a paradigm shift, and read them as being predicated on national and foreign stylistic traditions.

Subscription card included in the first issue of Cal, 1979. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Cover of issue 3 of Cal, 1979. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

This section of Cal reported on different aspects of cultural activity through brief questionnaires addressed to prominent agents of the cultural field. The spread displayed here, from issue 3 of Cal, 1979, addresses the topic of art criticism in Chile. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

This section of Cal reported on different aspects of cultural activity through brief questionnaires addressed to prominent agents of the cultural field. The spread displayed here, from issue 3 of Cal, 1979, addresses the topic of art criticism in Chile. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Later issues of Cal foregrounded photography, not only by inviting photographers to write and publish their work, but also by featuring theoretical articles that engaged the medium through acute reflection.

Her article’s appraisal of the state of Chile’s plastic arts in 1978 sheds some light on Richard’s later contributions to Cal and on her policy as the editor of issues three and four. For this reason, it is worth taking a closer look at some of her views and their implications. According to this influential critic, “a new way of problematizing art in Chile” 13 had come into view through a series of group exhibitions. A distinctive feature of this new approach was the widespread use of photographic resources by artists, although Richard noted that this was often done irresponsibly by those who relied on “photography (practice) as a mere technical means, with no degree of awareness as to the function of photography (theory) as an ideological vehicle.” 14

Accordingly, later issues of Cal foregrounded photography, not only by inviting photographers to write and publish their work, as in the cases of Jaime Villaseca (on the third issue) and Paz Errázuriz (on the fourth) but also by featuring theoretical articles that engaged the medium through acute reflection. Two crucial articles stand out in this context; the first is “América=Topo/grafía foto/gráfica (efecto de las primeras intervenciones fotográficas en el Nuevo Mundo)” by the poet, theorist, and visual artist Ronald Kay, later included in one of his most important books, Del espacio de acá: señales para una mirada americana [1980], a compilation of texts written between 1972 and 1979. The second, “Sobre la fotografía de Susan Sontag: algunos textos traducidos” by Adriana Valdés, is a composition of translated extracts from Susan Sontag’s book On Photography, published in 1977, which compiles six essays originally published in the New York Review of Books between 1973 and 1977. The author’s intention was to share information that could then be used “as working material by others.” 15

These two texts, along with Dávila’s essay on the nude and an article titled “W. Benjamin: el hombre a la intemperie” (W. Benjamin: Man Out in the Open)—a portrait of the prominent German thinker penned by the literary critic Martín Cerda—all demonstrate a penchant for fragmentary writing that seems far from coincidental. As Cerda points out, Benjamin witnessed a collapse of “panoramic views” that transformed his own perception of reality into a scattering of fragments or crumbs, leading to an effort to “reestablish a new network of meaningful connections between the scraps of reality. This explains not only his obsessive interest in the insignificant but also his marked preference for incorporating aphorisms or fragments in his writing (to the point that—as Theodor W. Adorno remarked—he made the fragmentary into a principle of his thought).” 16

Such affinity with Benjamin’s methodology makes sense given Chile’s political climate at the time, fragmented as it was by political polarization and shocked to the bone by the collapse of democracy and the seizure of crucial spaces of social life (such as universities) by dictatorial authoritarianism. Fragmentary writing turns away from academic grandiloquence seeking—as Benjamin did—to create new meaningful connections; likewise, many artists felt the need to work out of a marginal position, using precarious means or their own bodies and opting for an aesthetics of the fragmentary that resisted the grammars of hegemonic power. These were the artists that Cal supported and that Richard regarded as “advanced.” 17

Two further remarks from Richard’s “Dos enfoques” piece are worth highlighting, both of them diagnostic. First, she notes a disconnect between Chilean artists who produced and exhibited their work abroad and the local context; second, she observes a “thorough expiration of artistic experiences akin to Surrealism, Pop art, and New Figuration. . . [which in her view stemmed from an] illusionist tradition of art.” 18 Richard argued that the function of art was to “critically intervene in a situation-life on the basis of the (real and not fictitious) spatio-temporal unity that structures it.” For this reason, she called attention to “the opening of new mechanisms of artistic production and communication whose aim was to radically modify the sociocultural habit that grounds the perception and understanding of traditional art.” 19

Both diagnoses reaffirm the cultural critic’s stance in favor of an art that is connected to its context, a position shared by several other contributors to Cal. A similar stance was voiced by the editors of the first issue, who spoke against any effort “to separate art from life, intelligence from sensibility, the artist’s studio from the man on the street,” 20 and it surfaces again and again in the responses printed in a section of the journal that examined various aspects of cultural life through brief questionnaires addressed to important players in the field. In one case, a group of people connected to the plastic arts were asked for their take on the state of art criticism in Chile (the section was accordingly titled “La crítica de arte en Chile”), and the replies include statements such as that by Gaspar Galaz, who claimed that "the first distinctive trait of national art, in most cases, is a militant engagement with life (individual and collective) and an attempt to modify and salvage new plastic media in order to unveil the complex contemporary human situation. . . . I believe that social life (taken as a totality) has made its repercussions felt by artists and in their activities. . . . I think that each of the latest movements or tendencies within the mutating world of the plastic arts is valid, as long as it is inserted within our reality. Only a critical thought inserted in visual thought can attain the validity and permanence required to promote the most diverse creative paths within Chile." 21

Another respondent was the artist Elías Adasme, who claimed that he understood “artistic practice as a way of acting within a system whose coordinates are innumerable and complex; and from there to become involved in the events that [he] had to experience, working with them and from them; as the protagonists of a time of emergency.” 22 This radical attitude was a necessity in a context of dictatorship, and the journal consistently endeavored to consider and expose that context—even in the text of a subscription card included in the first issue, where we read: “To read Cal is to take sides, in a world in which everyone does, to agree to fight for art, culture, and freedom.” 23

Richard’s categorical points of view were counterbalanced by Sommer’s remarks in his own diagnosis of the Chilean art field. Sommer sought to be more inclusive in his selection, not only by arguing in favor of artists based abroad but also by including artists who were part of those stylistic currents that Richard regarded as outdated. The critic acknowledges Eugenio Dittborn as one of the young creators who “authentically seem to function as beacons for their artistic travel companions,” 24 and has positive things to say about the work of Carlos Leppe and Catalina Parra, although for him they exemplified the “extreme avant-garde.” 25 He also offers positive appraisals of the Surrealist Rodolfo Opazo, the Pop artist Francisco Brugnoli, and claims that Ricardo Yrarrázaval is the best current Chilean painter. Sommer then turns to the question of expressive styles with links to foreign traditions, wondering: "[I]s there, in general, a single Central or South American country that has been capable of providing itself with a plastic language of its own? The answer to the question can only be categorically negative; to pretend otherwise would be shallow chauvinism, if not foolish blindness. Nonetheless, here in Chile such contributions—born, of course, in foreign lands—often achieve a physiognomy that is perhaps unique." 26

Nelly Richard’s manifesto “El arte en Chile: una historia que se recita, otra que se construye” (Art in Chile: A History to be Recited, Another to be Constructed), in issue 2 of Cal, 1979. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Cal’s second issue featured another important text by Richard, “El arte en Chile: una historia que se recita, otra que se construye” (Art in Chile: A History to be Recited, Another to be Constructed).

These claims stand for a rejection of the budding poetics of Chile’s local avant-garde (it is worth mentioning here that Sommer was an art critic for El Mercurio, a newspaper that supported the government during the dictatorship). Although we should be wary of generalizations that obscure the nuances of the discussion, at the time the response to these two diagnostic essays by Richard and Sommer gave rise to a polemic that would soon lead to partisan divisions.

Cal’s second issue featured another important text by Richard, “El arte en Chile: una historia que se recita, otra que se construye” (Art in Chile: A History to be Recited, Another to be Constructed). Here Richards responds to Sommer’s arguments and proceeds to articulate “the first program summarizing the postulates of the avant-garde regarding the material and historical pathways to be followed by new artistic and critical processes.” 27 In addition to broadening her own postulates, in this text Richard now also ventures to define some of her commitments as a researcher and curator. In that way, the essay functions as a manifesto of sorts: "Today, art in Chile must contribute to the development of its own history, supplementing its lack of critical forebears, RESPONSIBLY ACKNOWLEDGING THE EMERGENCE OF ITS CONFLICT IN HISTORY AS A CUT, A RUPTURE IN THE CONTINUITY OF THAT HISTORY." 28

Several critics and historians played a role in this conceptual reappraisal of the continent: Juan Acha, Marta Traba, Frederico Morais, Aracy Amaral, Jorge Alberto Manrique, Damián Bayón, Fermín Fèvre, Saúl Yurkievich, Néstor García Canclini, Mirko Lauer, Mário Pedrosa, Jorge Romero Brest, and Richard herself, among others.

Cultural agents were thus unambiguously called upon to come to terms with the emergence of an art that should demonstrate sufficient historical consciousness to introduce “creative processes on the basis of dynamized life-situations.” 29 This was ultimately a dispute regarding history and its discourses—not only those of art and official institutions but also those that pertained to social life as a whole. For that reason, Richard advocates for an understanding of art as a cultural fact and for critically engaging in the discursive position from which one speaks, since there are no innocent interpretations and each society is responsible for both: the history that it constructs and the history that it recites.

By this time the topic of this debate had spread as an urgent concern throughout Latin America. Richard and other critics of the day were conceptualizing Latin American art from a local perspective, reaffirming their discursive position, and defining their own categories of thought in order to theorize on it from the South. Her ideas are part of a discursive turn in Latin American art, manifested in a new awareness of resistance rooted in the affirmation of a Latin American subjectivity that challenged the claims of cultural centers to being the source of meaning and the place of enunciation of modernity.

Several critics and historians played a role in this conceptual reappraisal of the continent: Juan Acha, Marta Traba, Frederico Morais, Aracy Amaral, Jorge Alberto Manrique, Damián Bayón, Fermín Fèvre, Saúl Yurkievich, Néstor García Canclini, Mirko Lauer, Mário Pedrosa, Jorge Romero Brest, and Richard herself, among others. As Dagmary Olívar has argued, they all pursued similar aims with respect to the plastic arts in the region, although they took different routes according to their individual areas of concern and ways of understanding art and Latin America. 30 In any case, they all contributed to the debate about the specificity of the plastic arts in the continent, a debate that continued to develop over the following decade. 31

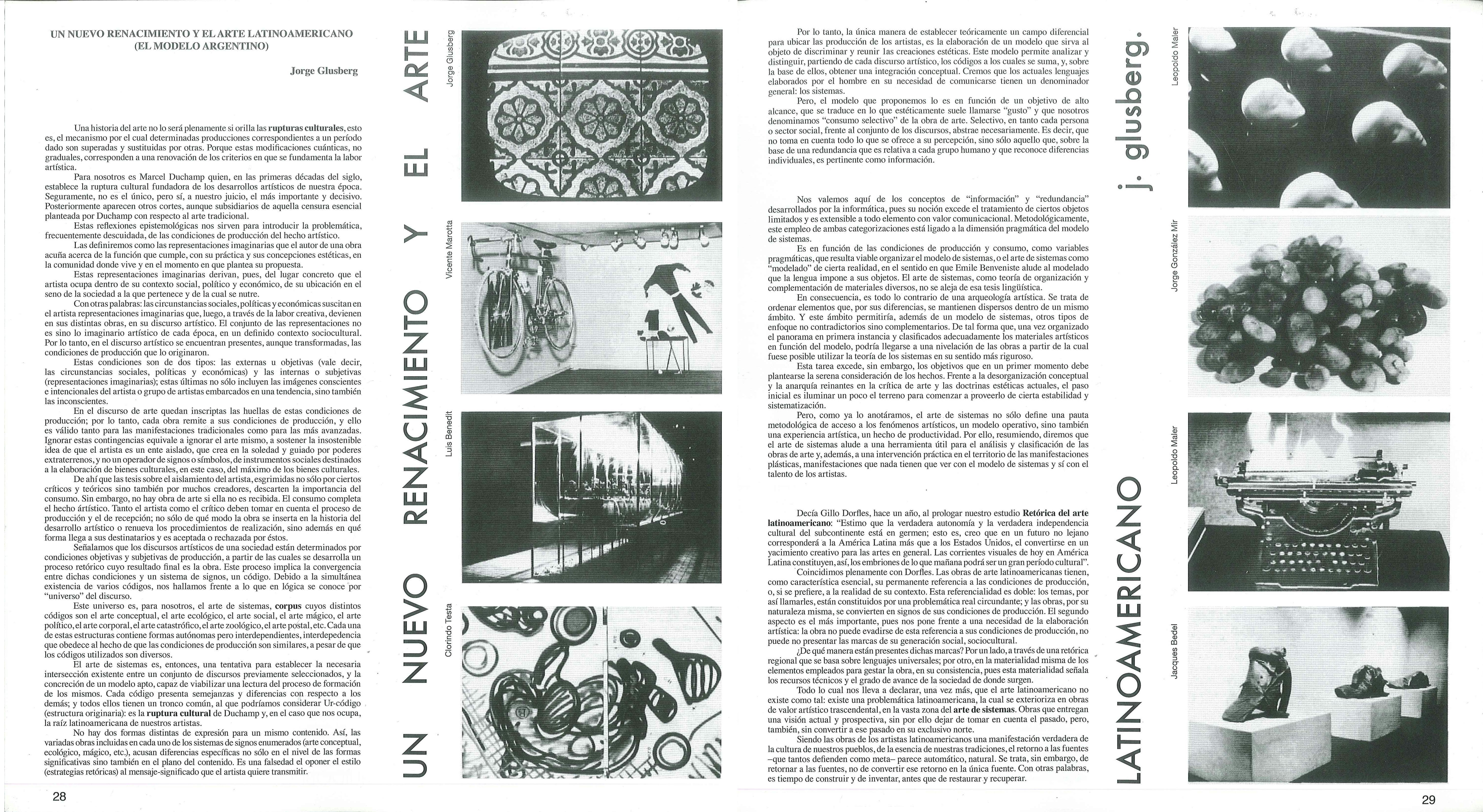

Jorge Glusberg's article “Un nuevo renacimiento y el arte latinoamericano“ (A New Rebirth and Latin American Art) in issue 4 of Cal, 1979. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

The third and fourth issues respectively featured “CAYC: información latinoamericana.”

This explains Cal’s efforts to disseminate the thinking of the Argentine critic and organizer Jorge Glusberg and the activities of the group known as CAYC (Centro de Arte y Comunicación). In the second issue, the journal published “Jorge Glusberg: el motor tras CAYC y otras actividades” (Jorge Glusberg: The Driving Force behind CAYC and Other Activities), a portrait of the critic written by Nena Ossa, who worked as conservator at Chile’s Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, in Santiago. The third and fourth issues respectively featured “CAYC: información latinoamericana” (CAYC: Latin American Information), previously published in the Italian journal Art Dimension Art in 1978, 32 and “Un nuevo renacimiento y el arte latinoamericano (el modelo argentino)” (A New Rebirth and Latin American Art [The Argentine Model]) signed by Glusberg himself. The two texts reported on the coming together of the collective initially known as the Grupo de los Trece (Group of Thirteen), which later renamed itself the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC). They also discussed some of their principles, kindred in spirit to Cal’s editorial line. As an example, Glusberg argues that "[a]n essential characteristic of Latin American artworks is a sustained reference to the conditions under which they are produced, or, if one prefers, the reality of their context. This referentiality is twofold: their subject matter, if I may so call it, is a problem taken from their environing reality; and also the works themselves, by their very nature, come to function as signs of their conditions of production. The second aspect is most important, since it confronts us with something that calls for artistic elaboration: the work cannot elude this reference to its conditions of production, it cannot fail to present the marks of its social, sociocultural coming into being." 33

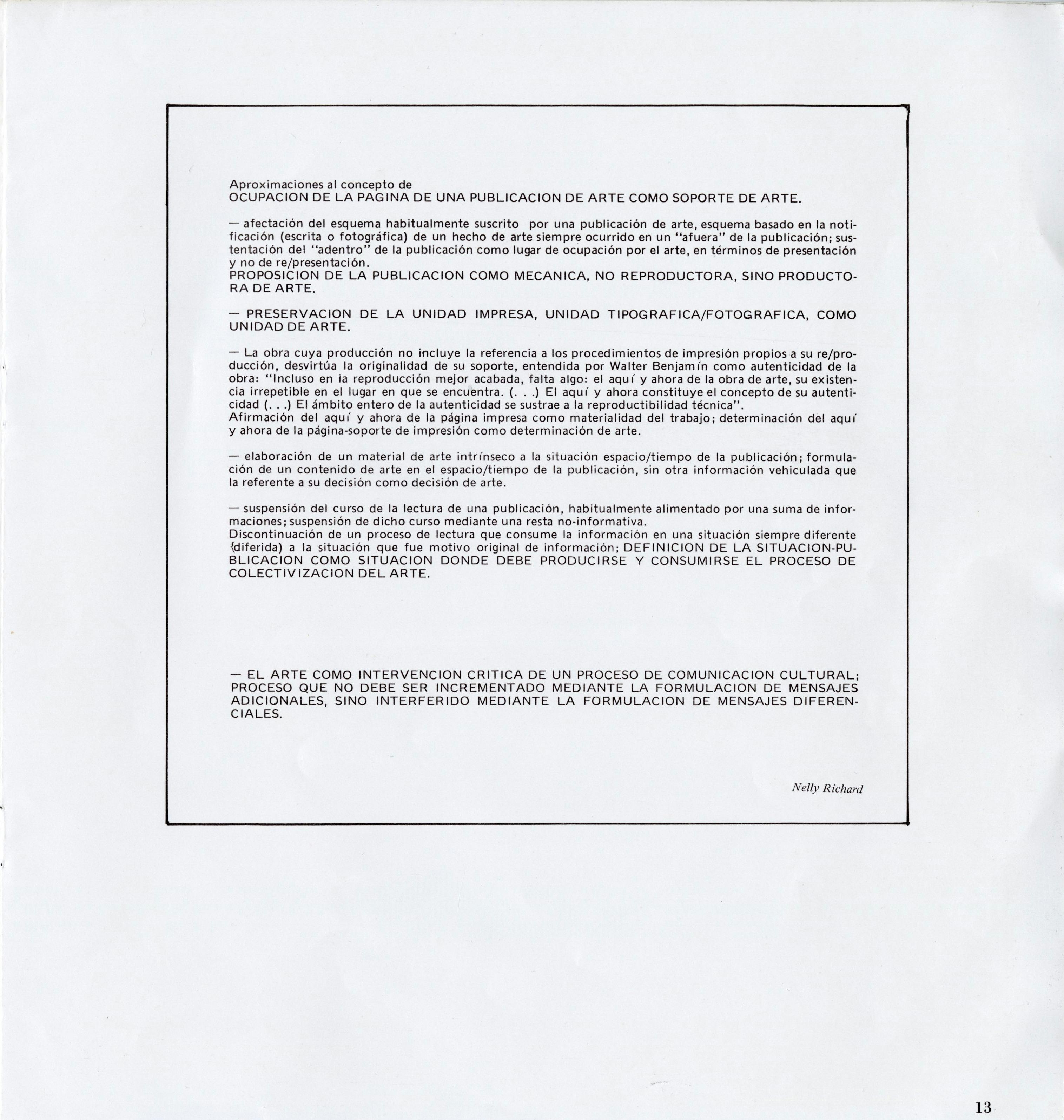

Nelly Richard’s article “Aproximaciones al concepto de OCUPACIÓN DE LA PÁGINA DE UNA PUBLICACIÓN DE ARTE COMO SOPORTE DE ARTE” (Approaches to the Concept of Occupying The Page of An Art Publication as Artistic Support) in issue 1 of Cal, 1979. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

“Page occupation” by Carlos Leppe, in issue 2 of Cal, 1979. The banner on the opposite page is an ad for an exhibition in which Leppe would perform the Action “La Estrella.” Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

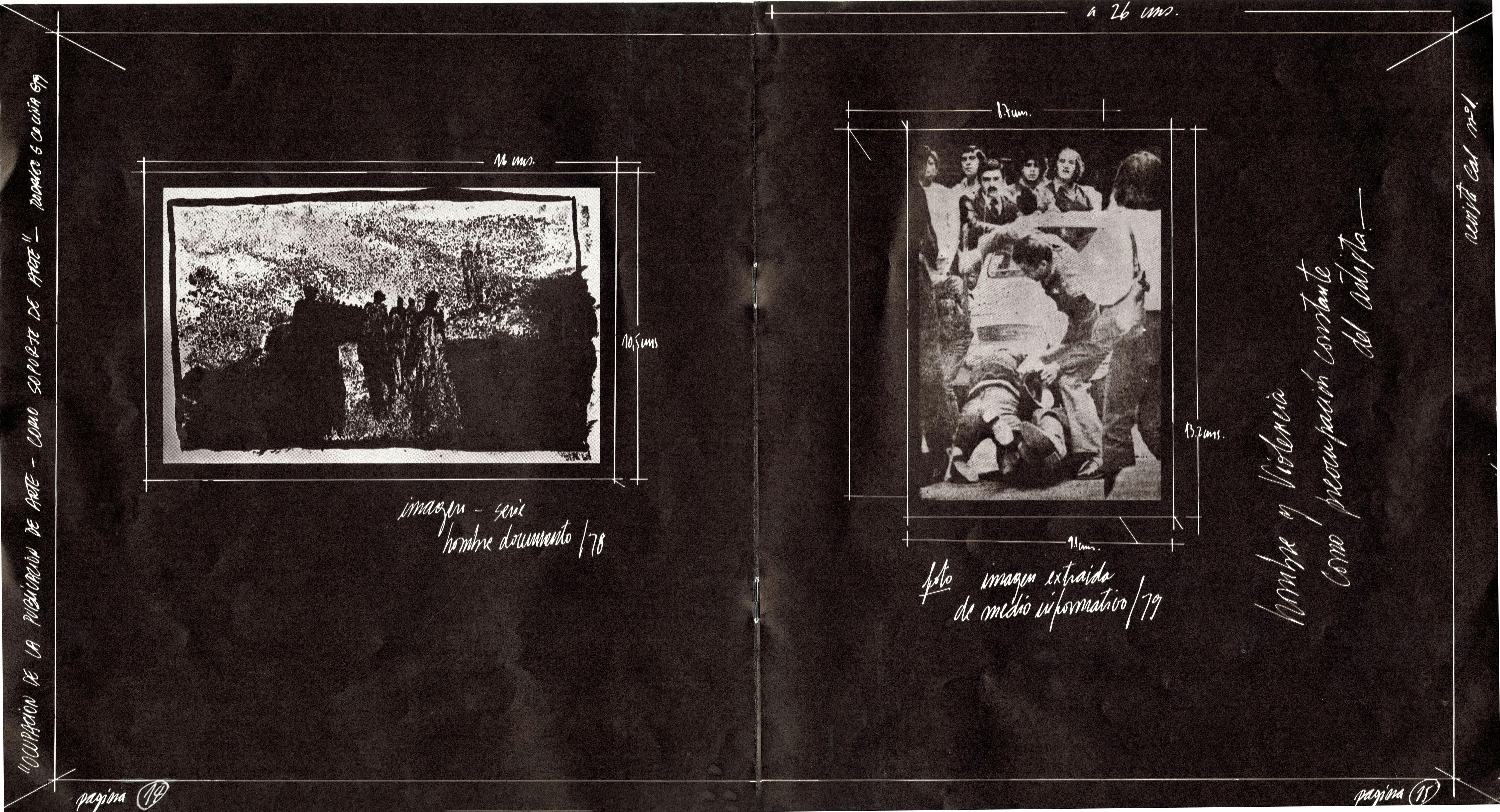

“Page occupation” by Rodrigo Cociña, in issue 1 of Cal, 1979. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives

Cal’s design set a landmark in Chilean art and culture journals. Some of its innovations were the use of a large square format and high-contrast black-and-white images, and the impersonal neutrality of printed matter, documentary and informative materials, newspapers, photography and film.

The work of the CAYC group introduced a shift in artistic and discursive practices and played a decisive role in the development of Latin American Conceptualism and in the discussion regarding the identity of Latin American art. In its fourth issue, Cal explored the work of yet another group, in an article by María de la Luz Hurtado titled “Ceneca= Centro de Indagación y Expresión Cultural y Artística” (Ceneca= Center for Cultural and Artistic Inquiry and Expression). The article reports on a project created in 1977 whose “main purpose was to assemble a group of professionals—sociologists, communicators, anthropologists, historians, sociocultural organizers, and authors—to reflect on and investigate the cultural and communication processes that have sprung up in the years after the coup in September 1973.” 34 The avant-garde and collaborative vocation of the projects reviewed are clearly indicative of the journal’s elective affinities, which informed not only the content selected for publication but also its design. 35

Cal’s design set a landmark in Chilean art and culture journals. Some of its innovations were the use of a large square format and high-contrast black-and-white images—reminiscent of the various resources of advertising posters, slogans painted on walls, and the impersonal neutrality of printed matter, documentary and informative materials, newspapers, photography and film—, the arrangement of titles in different directions over the page, visually charged backgrounds, the use of a wide set of fonts in a manually achieved layout where collage, Letraset, and technical draftsmanship coexisted. 36

Another essential component of the journal was the section titled “Aproximaciones al concepto de OCUPACIÓN DE LA PÁGINA DE UNA PUBLICACIÓN DE ARTE COMO SOPORTE DE ARTE” (Approaches to the Concept of Occupying The Page of An Art Publication as Artistic Support). The section—conceived by Rodrigo Cociña and Teresa Gunther—meant to introduce original artworks as intrinsic constituents of the publication, and its guiding premise was established in a manifesto of sorts, signed by Richard, some of whose proclamations would become programmatic principles of Chilean Conceptualism: “Art as critical intervention in a process of cultural communication; a process that must not be added to through the formulation of further messages, but interfered with through the formulation of differential messages.” 37

The first artist to occupy the page was Cociña, who arranged two images that, although visually hazy, clearly alluded to the political violence that the country was going through. In the second issue, it was Carlos Leppe’s turn; his aim was to design an alternative cover for Cal, and to this end he covered most of the page with a blown-up fragment of Richard’s manifesto “El arte en Chile: una historia que se recita, otra que se construye,” over which he set the words “LEPPE X CHILE” in large bold type. Carlos Altamirano took over the section in the third issue, and like Leppe, he occupied the page with yet another excerpt from Richard’s manifesto, now accompanied by a questionnaire that readers could cut out. Readers were asked for their thoughts on the following assertion: “The history of Chilean painting is the history of a successive appropriation of what is foreign, a history that was never thought from ‘within’ what is our own as a source of tension with what is foreign.” As explained in the questionnaire, Altamirano was requesting readers to fill it out and send it back, so that he could include their replies in an exhibition titled Revisión crítica de la historia del arte chileno como trabajo de arte (Critical Review of the History of Chilean Art as Artistic Work), to be held at CAL in the following weeks. Both Leppe and Altamirano were responding to Richard’s call for creating art that could take on the challenge of thinking and building its own history.

The last occupation was by the artist Catalina Parra, who unlike her predecessors published a puzzling image—hard to decipher—which, following Richard’s program, aimed to “suspend the process of reading the publication, usually nourished by an addition of information; a suspension of that process by way of a non-informative subtraction.” 38

Undoubtedly, all information regarding Cal’s plastic arts section contributes to an analytical understanding of the ways in which Latin American Conceptualism developed and was theorized. In Chile’s unique context, at a time when creative and intellectual activity was drastically curtailed, the journal not only took on the task of fostering a space for the exchange of ideas between diverse cultural actors but also set out to foreground and promote cultural practices that were not being instrumentalized by the regime, which for the sake of suppressing all forms of dissident expression co-opted all channels of alternative communication. Cal decidedly stood up to the regime and engaged head-on in a discursive dispute that impacted not only how art was practiced and discussed but also the lives of hundreds of people who were subjected to the terror and impoverishment unleashed by the dictatorship. The steadfast commitment on the part of Chilean avant-garde artists to connect art and life, and the theoretical positioning of some cultural actors who embraced the challenge of building their own history, were not merely discursive concerns. On the contrary, they enacted a vital and conscious stance with regard to the political and cultural circumstances of the time, one that permeated all forms of artistic and intellectual production.

It has not been possible to locate the copyright holders, despite having carried out a diligent search. ISLAA makes itself available to right holders to agree on the content of the legal notice.