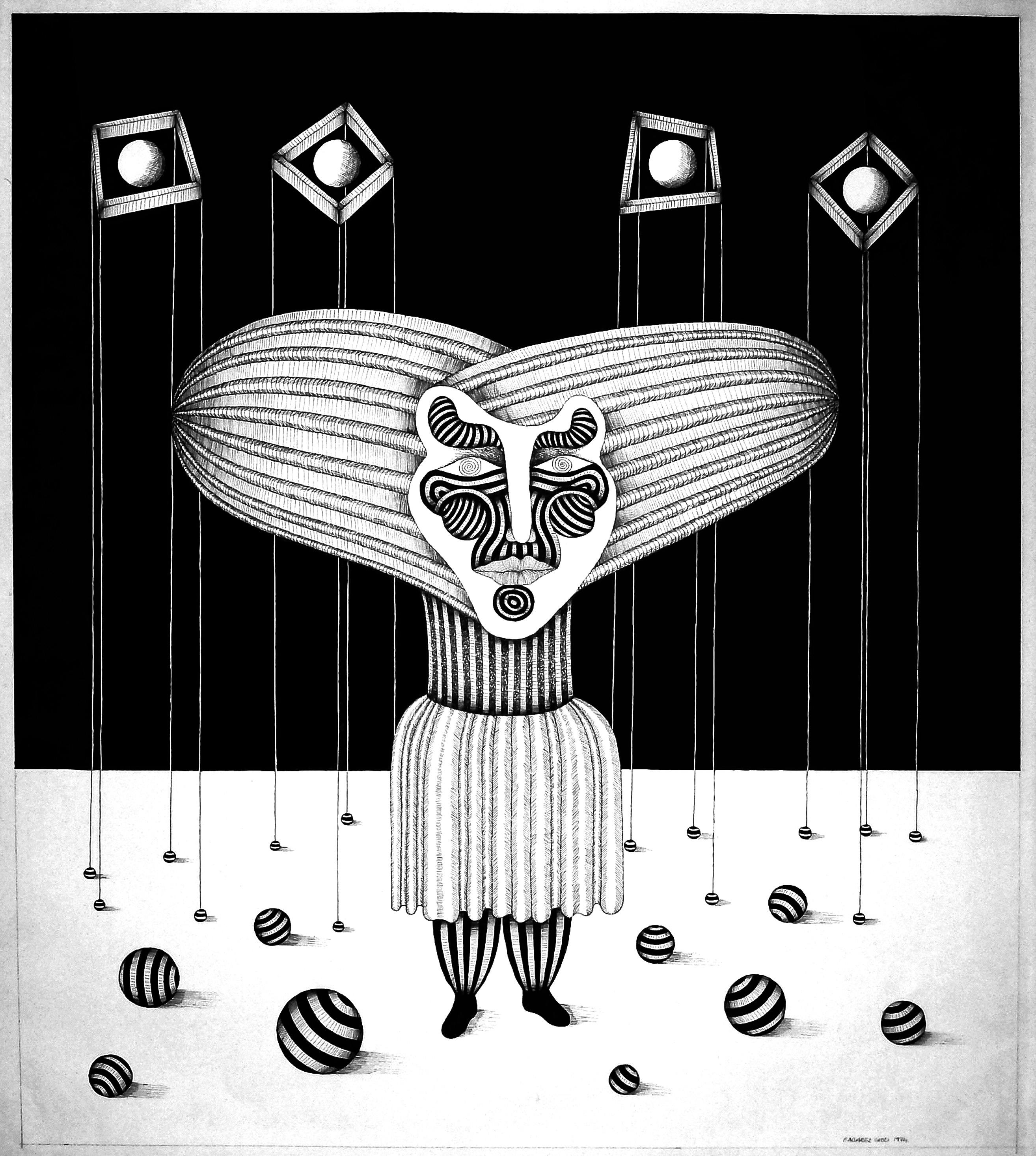

Domingo Ferreira, Untitled, 1972. Ink on paper, 15 7/8 × 13 5/8 in. (39.7 × 34 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

Fig. 1. Hermenegildo Sábat in front of his work Por fin se murió (At Last He Died), 1965, at the Salón de Pintura Moderna del Instituto General Electric (IGE), Montevideo, 1963 or 1965. Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales, Montevideo. Photo: Alfredo Testoni

Fig. 2. Jorge Páez Vilaró, Asamblea partidaria (Party Assembly), 1966. Enamel on canvas, 48 × 64 in. (120 × 160 cm). Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales, Montevideo

Fig. 3. Jorge Páez Vilaró, La niña Gabriela sueña con monstruitos (Little Gabriela Dreams of Little Monsters), 1968. Oil on canvas, 80 3/4 × 63 1/2 in. (205 × 161 cm). Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales, Montevideo

From the Desk of … invites scholars to fill gaps in English-language reference materials on Latin American art by developing research on movements, geographies, and methodologies.

From 1920 to 1950, the visual arts in South America presented resonances with the kind of realism practiced by Mexican muralists like David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, but they also displayed influences from European artistic movements such as Expressionism, Surrealism, and Post-Cubism. During this eclectic period, socially oriented realism focused on representing human figures. These figures were either idealized—highlighting their utopian potential—or portrayed as victims in Indigenist interpretations. This artistic approach aimed to uncover traces of a new form of humanism within the distorting reflections of secular colonialism and the militaristic brutality that marked the twentieth century.

In the context of Río de la Plata, this stereotypical realist model faced a definitive crisis in the 1960s, coinciding with a crisis of its underlying subject. The emerging art agents, primarily from the urban middle classes, found themselves in conflict. On one hand, they were drawn to promises of emancipation; on the other, they were caught in the grip of consumerism and the chaotic communication of mass media. This hypercritical subject had to construct itself within an ethical framework that was able to combine hope and hopelessness, cynicism and humor. The Nueva Figuración movement emerged in the Río de la Plata region out of this semantic field. Featuring a transgressive form of figuration, it critiqued the classical canon through distorted images of the body, blending human and animal elements, and juxtaposing the lyrical with the bestial.

Of course, this approach was not new in Western iconography. Some of its metropolitan predecessors included the spectral figures of James Ensor, Edvard Munch, and Emil Nolde. Additionally, closer in time were artists like Henri Michaux, Jean Fautrier, Francis Bacon, and the CoBrA group, whose works offered a biting critique of the prototypical modern subject.

In Argentina, the paintings created by young artists who began to gather and exhibit their work after the fall of President Juan Domingo Perón in 1955 captured the attention of French critic Michel Ragon, who coined the term “Nueva Figuración” to describe their style. The most advanced group that followed this direction—which included Luis Felipe Noé (Buenos Aires, 1933), Ernesto Deira (Buenos Aires 1928–Paris 1986), Jorge de la Vega (Buenos Aires, 1930–1971) and Rómulo Macció (Buenos Aires 1931–2016)—first showed in Buenos Aires in 1961. Their aesthetic style gained momentum in the 1960s, fueled by a vibrant expressionism that melded the legacies of Surrealism, Action Painting, and Pop art. Felipe Noé stated: “The human figure, immersed in chaos, gains a new meaning and purpose.” 1

In Uruguay, this type of figuration did not break entirely with traditional painting, unlike the Argentine group, particularly Noé. In fact, their main format was not painting but drawing, which reached its height with a wave of artists who emerged at the end of the decade. The middle-class sector, which included most artists and intellectuals, assumed an unprecedented political and cultural role. At the same time, like the urban working classes, they were impacted by a social and economic crisis that escalated and ultimately led to the most profound institutional collapse the country experienced in the twentieth century during the 1970s.

In this essay, I will consider the years 1960–80 as the Nueva Figuración cycle in Uruguay, which unfolded both in painting and in the graphic arts as a response to specific political, social, and cultural circumstances. This local context was crucial for the emergence of this movement, which was further influenced by other regional resonances. In February 1960, several Argentine drafters exhibited their work in Montevideo, among them Jorge Mattalía (Entre Ríos, Argentina, 1931–Cosquín, Argentina, 1980) and Julio Martínez Howard (Entre Ríos, Argentina, 1932–Buenos Aires, 1999). A journalistic piece detailed that work by these artists shared a “common expressive feature: they violently manipulated and deformed the human figure with the intention of achieving an extreme expression.” 2

In July of the same year, the Instituto Cultural Uruguayo-Brasileño showed drawings and engravings by Marcelo Grassman (São Paulo, 1925–2013), an artist who, according to the press, displayed a “critical and sarcastic grasp of reality, featuring invented figures that blended human, animal, and monstrous elements.” 3

Additionally, in 1963, the four members of the Argentine group exhibited in Montevideo. They shared with the Uruguayan artists a cultural context conducive to a skeptical and caustic perspective on the human condition.

In Uruguay, this pictorial current emerged in parallel to Matter Informalism, as some of these painters began to include android forms in their work, while others, outside of this tendency, started to practice a grotesque and sardonic figuration.

In the graphic arts, this style first emerged in journalist illustrations and printmaking, which led, in the second half of the 1960s, to a group of artists focusing on independent drawing. These artists soon exhibited a distinctive blend of irritating irony and dark humor, embodying an iconoclastic spirit that challenged the established aesthetic and moral norms of society.

The Nueva Figuración cycle in Uruguay unfolded in 1960–80 both in painting and in the graphic arts as a response to specific political, social, and cultural circumstances.

The emergence of this critical attitude formed a cultural link between that group of writers and the artists who were adopting a new form of figuration in the visual arts.

Fig. 10. Manuel Espínola Gómez, Plus (Por los uruguayos silenciados) (Plus [For the Silenced Uruguayans]), 1974. Graphite and crayon on paper, 25 3/16 × 39 3/8 in. (64 × 100 cm). Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales, Montevideo

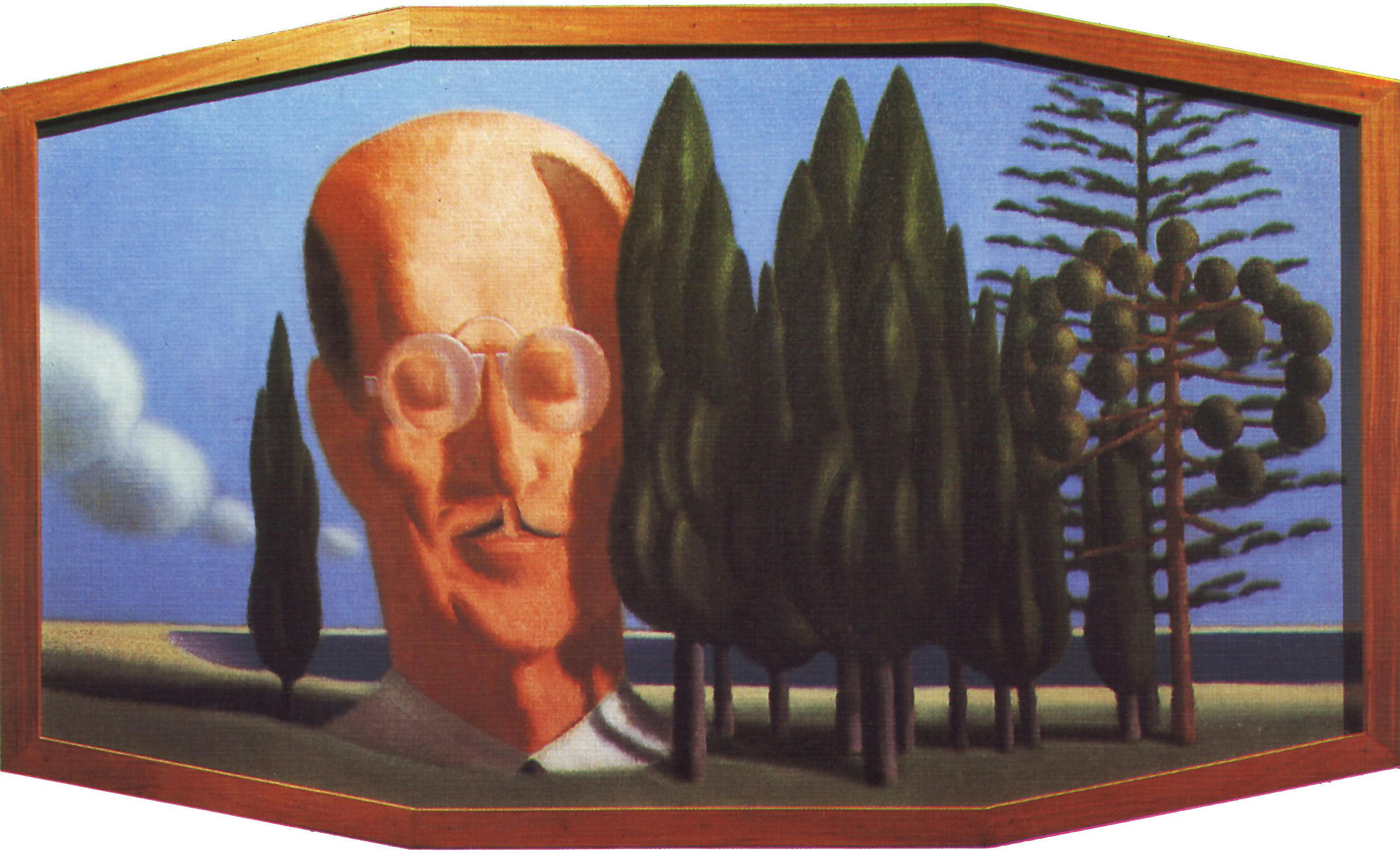

Fig. 11. Manuel Espínola Gómez, Paisaje encabezado (Headed Landscape), 1978, from the series Polifocalismo, 1977–78. Oil on canvas, 36 5/8 × 63 in. (93 × 160 cm). Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales, Montevideo. Courtesy Comisión del Bicentenario

Fig. 12. Haroldo González in front of his work La reacción (The Reaction), 1969, at his exhibition at Galería U in Montevideo, August 1970. Haroldo González Archive. Courtesy the artist

Fig. 13. Haroldo González, Untitled, 1979. Painting and collage, 27 9/16 × 35 7/16 in. (70 × 90 cm). Courtesy the artist

Nueva Figuración in Painting

Hemenegildo Sábat (Montevideo, 1933–Buenos Aires, 2018) started drawing for print media in the newspaper Acción, in Montevideo, where he met writer Juan Carlos Onetti (Montevideo, 1909–Madrid, 1994), in 1955. This early connection proved influential. Onetti, a central figure of the so-called Generación del 45, belonged to an intellectual group known for their rigorous self-criticism. Their approach varied from a refined sense of humor to a deeply pious pessimism. Mario Benedetti (Montevideo, 1920–2009), another member of this cohort, published El país de la cola de paja (1960), a satire that critiqued Uruguayan idiosyncrasies and, more importantly, served as a cautionary tale about the crisis facing “welfare society,” which symbolized Uruguay’s historical cycle from 1920 to 1960. The emergence of this critical attitude formed a cultural link between that group of writers and the artists who were adopting a new form of figuration in the visual arts. 4

A series of oil paintings by Sábat from 1962 represents one of the earliest visual manifestos of Nueva Figuración. These works focus on the representation of an embryonic subject that verges on the monstrous. In 1960, on the occasion of Sábat’s first exhibition, an art critic said: “Sábat is able to convey … that pathetic expressionist impetus of his temperament … arising from a dramatic confrontation with the world, a sense of reality’s absurdity, a singular interpretation of human gestures and attitudes …” 5

Since 1963, Sábat created works that featured an accumulation of faces and bodies, shifting his satirical lens to the whole collective body (fig. 1). This approach would be later adopted by Heber Rolandi (b. Montevideo, 1936) and Jorge Páez Vilaró (Montevideo, 1922–1994). Páez joined Informalismo in the early 1960s, closing its cycle with the incorporation of anthropomorphic representations to the surface. Around 1964, he painted heterogeneous sets of facemasks as an ironic characterization of mass society, particularly targeting the collectives ensnared within political parties (fig. 2). While some of his works appear to align with Pop art, they simultaneously diverge from this movement and seem, in part, to draw closer to the legacies of CoBrA. Páez Vilaró emphasizes expressionist patterns in his depictions of tango and slum scenes, where the dramatic aspects of social marginality are diluted within the folkloric and festive nature of the scenes portrayed (figs. 3 and 4).

Since the 1950s, metropolitan avant-garde movements such as Pop art and Op art, which focused on the study of optical effects and the iconic representation of object-commodities, influenced Nueva Figuración through formal borrowings. However, these influences did not change the strong expressionist drive or the poetic-metaphysical concerns prevalent among most of these Uruguayan artists. A key influence for these artists, whether conscious or not, was the wandering existentialist ghost (in its Heideggerian form, and later in Sartrean variations) that was haunting the local intellectual milieu throughout the 1950s and much of the 1960s, creating an atmosphere where it intersected with the demanding social violence of the period. In such context, artists combined fantasy and dreams with the provocations, at the same time joyful and angry, of the grotesque. This was related, on the one hand, with the sarcastic gestures of 1960s youth culture, epitomized by the deformed little men John Lennon drew and by Peter Blake’s psychedelic images, and on the other hand, the rawness of Magical Realist Latin American literature.

Ruisdael Suárez (Montevideo, 1929–2004) and Ernesto Cristiani (Montevideo, 1928–1989) were multifaceted artists who frequently exhibited together, showcasing their work across various mediums including drawings, paintings, engravings, and large-format objects. Critics from their era and later have broadly categorized Ruisdael Suárez and Ernesto Cristiani as “Pop artists,” often viewing them as derivatives of the North American trend (figs. 5 and 6). However, it must be noted that while their works display formal elements of Pop art, the settings in which the human figures are depicted emit a disturbing undertone that marks a fundamental distancing from this trend. Cristiani’s series of preoccupied faces (fig. 7) resembling pieces of wax, carry a metaphysical aura that becomes more pronounced when these faces are grouped in an abstract space. Suárez, despite working more within the formal boundaries of Pop art, employs Surrealist metaphors that occasionally suggest social themes (fig. 8). Towards the end of the 1970s, these artists favored a dreamlike style of painting, a trend also embraced by other painters like Manuel Espínola Gómez (Solís de Mataojo, Uruguay, 1921–Montevideo, 2003). While Espínola Gómez shared the younger drafters’ enraged attitude, by the late 1970s he had begun creating a series where the human figure transitioned into a Surrealist atmosphere (fig. 11).

During this period, the pursuit of a poetic encoding in images was connected to a burgeoning interest in linguistic matters among visual artists. This interest was fueled by the spread of recent publications on semiotics, structuralism, and conceptualism, particularly in Buenos Aires. The opening of the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC) in 1969 played a pivotal role in promoting the use of new resources for an art of ideas, bringing together artists from Argentina and several other Latin American countries.

One of the Uruguayan artists invited to CAYC was Haroldo González (b. Montevideo, 1941) who, besides creating drawings and audiovisual works, made paintings that resonated with the final stage of Nueva Figuración, when this tendency was beginning to diverge in various directions toward end of the 1970s (fig. 12).

González explored formal analogies between human body parts and mechanical objects, leading to a metamorphosis of the body and its transformation into a machine (fig. 13).

Fig. 14. Luis Camnitzer, Untitled, 1963. Ink on paper, 11 13/16 × 7 7/8 in. (30 × 20 cm)

Fig. 15. Luis Camnitzer, Untitled, 1963. Ink on paper, 7 7/8 × 11 13/16 in. (20 × 30 cm)

Fig. 16. Luis Camnitzer, Untitled, 1969. Ink on paper, 11 × 8 11/16 in. (28 × 22 cm). Luis Camnitzer Archive

Fig. 17. Luis Camnitzer, Untitled, 1969. Ink on paper, 11 × 8 11/16 in. (28 × 22 cm). Luis Camnitzer Archive

Ink drawings were the typical medium for illustrators working in print media throughout the 1960s, while xylography had been relevant in left-wing political media in the 1930s and 1940s, gaining momentum in Uruguay with the founding of the Club de Grabado in Montevideo in 1953.

Nueva Figuración in the Graphic Arts

Graphic artists engaged in Nueva Figuración primarily utilized two key techniques: wood or linoleum engraving, and ink drawing with the “rapidograph.” Additionally, artists like Hermenegildo Sábat and Alejandro Casares (Montevideo, 1942–Marindia, Uruguay, 2020) also employed an inked bamboo cane. These techniques were prevalent due to their ability to allow direct action on the medium, yielding almost immediate results. Ink drawings were the typical medium for illustrators working in print media throughout the 1960s, while xylography had been relevant in left-wing political media in the 1930s and 1940s, gaining momentum in Uruguay with the founding of the Club de Grabado in Montevideo in 1953.

In 1963, after completing his Guggenheim Foundation grant at the Pratt Institute in New York, Luis Camnitzer (b. Lübeck, Germany, 1937) returned to Montevideo. During an interview with Marcha, he shared anecdotes from his time as an engraving artist in New York: “At Galería Sudamericana, I showed fat women, old men, object-women, and other little monsters one encounters on the streets … The curator from the Metropolitan Museum purchased my Feto con barba.” 6 The diverse and extensive fauna Luis Camnitzer encountered in New York inspired him to push the boundaries of absurdity in his graphic illustrations, which he was already producing for Marcha in Montevideo (consider Feto con barba [Fetus with Beard] as an example) (figs. 14 and 15). These “little monsters,” drawn in ink, echoed the sensibilities of Agustín Alamán (Tabernas de Isuela, Spain, 1921–Madrid, 1995. He spent many years in Montevideo), who incorporated humanoids into his strange matter paintings, and Hermenegildo Sábat, known for his portrayals of strange androids.

By the end of the 1960s, the virtuous dose of humor evident in Camnitzer’s early drawings evolved into gelatinous faces that appeared to parody the conservative bourgeois subject during revolutionary times (figs. 16 and 17). Asked about his possible links with the Argentine group, Camnitzer says: “My relationship with Yuyo [Felipe Noé] didn’t begin until 1964, when we shared an apartment in New York. But his influence was mostly intellectual and theoretical.” 7

Domingo Ferreira (b. Tacuarembó, Uruguay, 1940), a student of Luis Camnitzer at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Montevideo, started to show his work as illustrator for different periodicals in 1963. His biting critique of the bureaucratic conformist (figs. 18 and 19), reflecting the concept of the “one dimensional man” that Herbert Marcuse defined in 1954—which gained significant prominence in the following decade—was a major influence on the corrosive tendencies within the Nueva Figuración.

In mid 1964, Nelson Ramos (Dolores, Uruguay, 1932–Montevideo, 2006) visited Jorge de la Vega’s workshop in Buenos Aires alongside Jorge Páez Vilaró. This visit strengthened their ties to the Argentine group. An alum of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Montevideo, Ramos experimented with Informalist painting and, in the early 1960s, created anthropomorphic silhouettes using grease pencil, set against a backdrop of small signs characterized by energetic and scattered strokes. The works were Neofigurative drawings, but they closely aligned with sign graphisms that belonged to an abstract tendency.

Jorge Páez Vilaró also stood out as a draftsman—he was a friend and admirer of the Mexican Luis Cuevas. He achieved his greatest versatility in this medium between 1966 and 1970, during a period of expansion for Neofigurative drawing, which an art critic famously dubbed “Dibujazo.” 8 Although he adopted a grotesque style, he steered clear of the rage that typified the younger members of this movement. His drawings are instead rendered in a pleasantly mocking spirit, capturing with gentle humor various human prototypes and aspects of urban folklore: tango, cafes, and port suburbs (figs. 21 and 22).

In 1965, one of his earliest drawing exhibitions, Antropocalipsis de la Homocoteca (Homocoteca Anthropocalypse), marked a humorous departure from Sartre’s existential angst. Featuring circuses, hells, kennels, and carnival parades, the exhibition composed a theatrical frieze that turned the concept of the apocalypse into something laughable. The same humor infused Estampas de la suburbia montevideana (Stamps of Montevideo’s Suburbs, 1967) and Estampones ciudadanos (Citizen Stamps, 1968), where drawings elevated Río de la Plata identity myths into a vivid chronicle of mural proportions (fig. 23).

In 1967, one of the most prominent Uruguayan writers described the situation as follows: “The disintegration of liberal society, which had been Uruguay’s proudest creation, has only accelerated throughout 1967. It appears we are witnessing—and will continue to suffer from—a vertiginous process: beneath the masks that fall daily, we encounter faces twisted in sordid rictus, marked by pain, and prone to violent gestures …” 9 This paragraph seems to describe the drawings of some of the young artists that emerged that same year. In August, Hugo Alíes (Santa Fe, Argentina, 1945–Montevideo, 2019) showed his drawings at Galería U, under the direction of Enrique Gómez (fig. 24). Alíes’s work oscillated between lyrical restraint (fig. 25) and dramatic outbursts (fig. 26). But it also exuded, between these two extremes, a playful irony (fig. 27). These drawings confirmed what the critics of the time defined as “a new generation of drafters that caught the unsuspecting off guard … with their anguished or poetic worlds … [with] the incisiveness of their social critique, or the richness of their dreamlike universes.” 10 The article characterized Alíes’s drawings as “a rebellion against human form,” “a distortion that verges on the grotesque,” and “a sensuality of lurid appearance.” These traits could be attributed to nearly all members of the Dibujazo.

Eduardo Fornasari (born in Montevideo, 1946), one of the earliest and most notable members of this movement, began exhibiting his work in late 1966. However, his 1968 exhibition established him, alongside Alíes, at the forefront of figurative expressionism. He was the first artist to directly address social violence in his drawings (fig. 28), where large black stains mediate between different scenes, facilitating representations at various scales (fig. 29). His work exudes a slow temporality, and emanates pleasure in meticulously crafted details, creating scatological landscapes where the marginalized elements of affluent society and visceral exposures take center stage. The morbid fascination with viscera is also evident in the works of Nelbia Romero (San Borja del Yí, Uruguay, 1938–Montevideo, 2015) (fig. 30) and Marta Restuccia (b. Montevideo, 1937) (fig. 31). These two artists began exhibiting their works around 1970, with their art making clear allusions to opulent carnalities and organic tissues. Their pieces reflect a tortuous view of the human condition, capturing both vitality and eroticism, as well as lurking violence and hatred.

This dichotomy gave rise, on occasions, to a gloomy human figure appearing not only in drawings but also in woodcuts, such as those of Carlos Fossatti (Paysandú, Uruguay, 1928–Toulouse, France, 1981), who created haunting atmospheres and characters (fig. 32).

Although it featured a sordid style of figuration, the Dibujazo’s “bestiary” occasionally incorporated lyrical intentions, where the human figure still carried erotic and vital promises, even against a backdrop of underlying sarcasm (figs. 33 and 34).

In 1968, the year of the first student deaths due to police repression, the printmaker Leonilda González (Minuano, Uruguay, 1923–Montevideo, 2017) created a series titled Novias revolucionarias (Revolutionary Brides), where she transformed the traditional lyricism of the female image into a caricatured expressionism infused with deliberate political content (fig. 35). Further research is warranted, beyond the limited scope of this study, to explore the various conceptions of the feminist gaze among artists associated with the Nueva Figuración, at a historical moment when class issues often overshadowed gender issues.

Although it featured a sordid style of figuration, the Dibujazo’s “bestiary” occasionally incorporated lyrical intentions, where the human figure still carried erotic and vital promises, even against a backdrop of underlying sarcasm.

Fig. 36. Fernando Álvarez Cozzi, Los payasos de siempre (The Usual Clowns), 1974. Ink on paper, 18 ½ × 16 5/16 in. (47 × 41.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist

Fig. 37. Álvaro Armesto, Untitled, 1973. Ink on paper, 26 3/8 × 20 in. (66 × 50 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

Fig. 38. Haroldo González, Untitled, 1971. Ink on paper, 20 × 25 9/16 in. (50 × 65 cm). Courtesy of the artist

Fig. 39. Jorge Satut, Untitled, from the series Los homenajes (Tributes), 1974. Ink on paper, 10 1/4 × 13 3/8 in. (25.6 × 33 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), New York

Introspection, a hallmark of painterly Informalism, was also evident in Dibujazo. But the latter blended the psychological introspection with an ethical and critical dimension, a challenging stance emblematic of the period. In this vein, Fornasari stated: “Before, I wanted to unveil men’s psychological identity through a raw portrait of what lies under their masks. Now I want to paint them from the outside … The rage that is present in my drawings maybe comes from the impossibility of expressing … the world of contrasts and violence that resides within each of us.” 11 Along the same lines, Néstor Canessa (Montevideo, 1944) said: “Little by little, I sought the most complex aspects of the inner world, and everything that is monstrous about our everyday experience … If I draw a head, I must draw it open—I perceive it as formless, I feel it as rotten.” 12

The opinions expressed by the drafters coincided in explaining that the choice of drawing was motivated by its immediacy. “If I don’t immediately put an idea on paper, to me it becomes corrupted,” said Heber Marchisio (Montevideo, 1943). [Gilmet and Peluffo, 25.] Jorge Satut (Montevideo, 1939–2013), confirmed this view: “Drawing is the most direct source of expression, when stimuli are so peremptory.” [Gilmet and Peluffo, 25.] This sense of urgency was fundamentally linked to a social context whose inevitable exhaustion appeared imminent in 1970: “There was an inexorable feeling that we needed to adopt forms of participation and engagement… which then pushed us to move faster than our own feet could carry us.” 13

Many works by Dibujazo artists display influences from comics, graphic design, advertising, and iconic elements of the culture industry, since the young drafters were avid readers of magazines (fig. 36 and 37). There were also instances in which the reflection on drawing as a language led to an approach to conceptualism, considering this term in a broad sense. Haroldo González’s graphic work, operating with diagrams and ideograms, is an example of this tendency. This is the case of a series of drawings that the artist divides into two hemispheres: an upper one, where the agent of power operates, and a lower one, where the domain over which this power is exerted unfolds (fig. 38). Jorge Satut, through his drawings, reflects on drawing as a form of representation and considers the image market as a means of speculating with the copy. This artist, the only one with hyperrealist intentions within the local Nueva Figuración group, appears to echo Walter Benjamin by representing icons of Western art transformed into commodity-images. However, he achieves this through manual reproducibility (figs. 39 and 40).

Despite their varied approaches to experimenting with visual languages, all the Dibujazo artists seemed haunted by a strange and abject element within the social organism, to which they sought to respond. This apocalyptic specter only fully revealed itself with the dismantling of democratic institutions in 1973, followed by years of silence, social disintegration, and collective forgetfulness. This fact led to Dibujazo’s becoming blurred in the cultural map. The year 1980 was a pivotal one for social and political perspectives, when civic and military authoritarianism was defeated through a popular referendum. There began a gradual cultural “coming out,” although there were inhibitions due to the repressive atmosphere within which this opening was paradoxically taking place. Several artists of the Dibujazo cohort continued their practice and bore witness to a shared mood that combined desire and anger, hope and frustration, due to the impossibility of achieving justice.

To describe this tendency further, I will return to two artists already mentioned: Hugo Alíes and Domingo Ferreira. While maintaining the graphic poetry that characterizes his work as a journalistic illustrator, Ferreira also delved into the chaotic universe that dominated his generation, a theme that he approached with humor and the passionate outburst typical of a survivor (fig. 41).

Alíes, for his part, turned to an expressionist style marked by fleeting and exacerbated lines. The android, emblem of Dibujazo, reappeared here marked by disillusionment and disbelief in the face of a lost future. The graphic narrative unfolding through this artist’s personal trajectory pays homage to a social cycle that began with the critical and irreverent attitudes typical of the 1960s. Twenty years later, it culminated in the raw satire of a collective disillusionment that Alíes directed angrily against himself (figs. 42 and 43).

The significant role of alternative galleries and art criticism in shaping the public image of young artists raises the question of whether Dibujazo was an overrated phenomenon, a result of the promotional and circulation avenues that emerged and established themselves in Montevideo during this period.

Indeed, the emergence of Nueva Figuración tendencies in drawing and painting coincided with a period characterized by a proliferation of cultural offerings, the institutionalization of visual arts, and the growth of a robust publishing industry that introduced new national writers and artists.

In November 1962, the Instituto Cultural General Electric of Montevideo, directed by Ángel Kalenberg, opened its doors. In June 1965, the Centro Uruguayo de Promoción Cultural (CUPC) was inaugurated under the direction of the Spaniard Benito Milla—who was also the owner of the Alfa publishing house, founded in 1958—and Enrique Gómez was its director of exhibitions. In 1967, Gómez became director of Galería Alfa and Galería U. In these roles, he not only brought together the youngest avant-garde artists but also became a key figure in promoting and commercializing their works, contributing significantly to the institutionalization of innovative artistic practices, primarily those associated with Nueva Figuración. His efforts transcended national boundaries: through Galería U, he orchestrated over twenty exhibitions in Buenos Aires between 1965 and 1974. Additionally, he played a significant role in organizing exhibitions for Uruguayan artists in the United States, due to his friendships with José Gómez Sicre (director of the OEA’s Departamento de Artes Visuales) and Armando Zegri, director of Galería Sudamericana in New York.

Three decades later, Eduardo Fornasari reflected on the Dibujazo phenomenon: “This was an art impelled to occupy a central position with the complicity of the entire cultural system of the time, perhaps before it had achieved the necessary maturity.” 14

This retrospective view of a key protagonist might convey a personal impression that the drafters might have—willingly—submitted to the overarching influence of advertising agents. However, an analysis of the connections between Nueva Figuración and the social, political, and cultural context that gave it significance suggests another hypothesis to explain the prominence of drawing in the artistic scene of the time. In fact, even if its visibility was promoted by emergent institutions, its necessity did not stem from these external demands. It responded to a collective awareness of shifting values and changes in intersubjective relationships, along with the perception of a new and urgent temporality in the social, already tinged with the impatience of history.